Chicken Wire Mechanics for a Large Vase Arrangement for the Professional Florist

Glass vases have been at the forefront of floral decorating for many years. Florists have learned how to create stunning designs using them, employing floral foam, interlaced stems, and other mechanics and techniques. It is important to practice with a variety of mechanics and make them part of your professional design repertoire. This knowledge is worth the time investment if your favorite mechanic becomes unavailable.

Mechanics

There is newfound interest in alternatives to fresh flower foams. Some designers are using chicken wire, also called poultry netting, as a substitute for foam. Before we address floral foam and chicken wire use, it is important to understand the definition of the term mechanics. The American Institute of Floral Designers (AIFD) defines mechanics as

a collective term for devices or techniques that help to secure materials and create stability in a floral composition. Mechanics are ordinarily concealed but may be deliberately exposed for artistic effect. Sound mechanics are the foundation for good design work.

Fresh Flower Foam

Phenolic floral foams are made from petroleum. They contain compounds that leach from the foam into the water-holding solution in which they are soaked. One of these compounds is a trace amount of formaldehyde.

Floral foams are safe to use, but some shops have soaking bins that are not regularly emptied and sanitized. If the soaking bin is not drained and cleaned after use, the compounds can concentrate in the water. Another problem with this practice is that microbes can grow in the soaking-bin water. Microbes lead to stem blockages that shorten vase life—the time that flowers remain beautiful and usable.

The best practice for hydrating fresh flower foam is to soak only the amount needed for the day. At the end of the day, dispose of the water and sanitize the bin with a quaternary ammonium (quat) disinfectant. Such cleaning

solutions are available from floral supply companies. If these are not available, a household detergent is the next best thing.

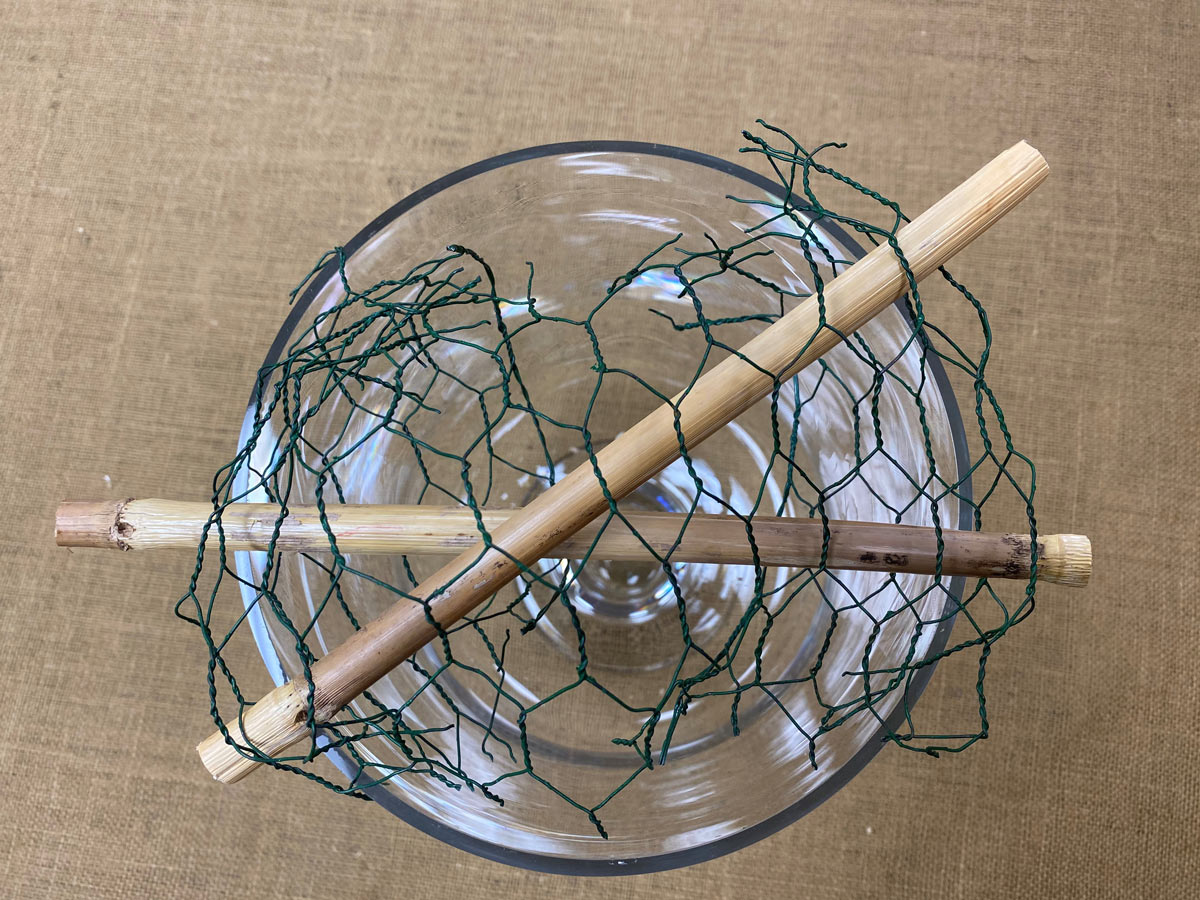

Chicken Wire

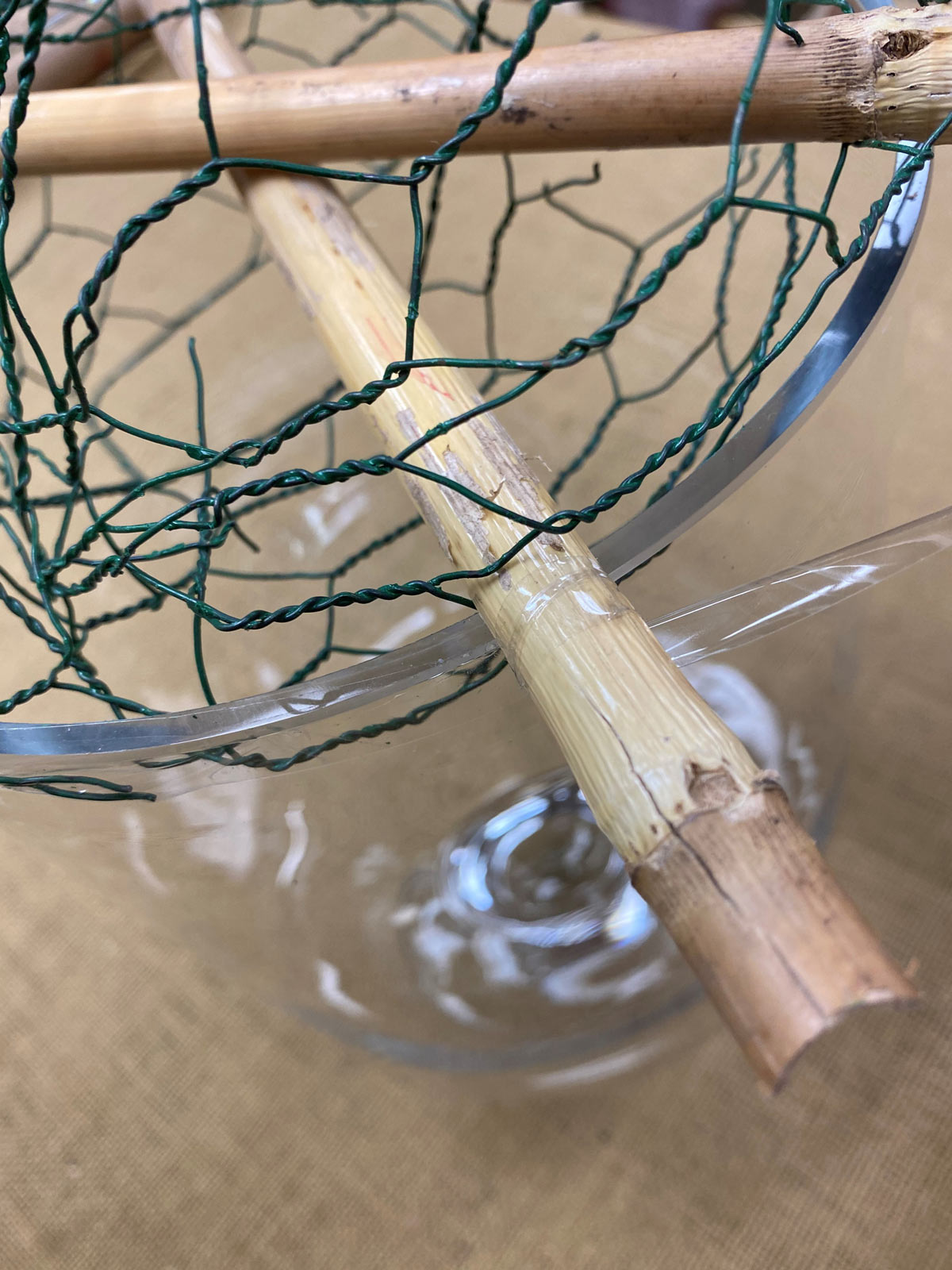

This mechanic preceded floral foam in floral design history. It is added in layers or stuffed into a container. It is important to fold it so that stems penetrate at least two layers of the wire, with an approximate separation of about 1 inch between levels. Multiple layers of the wire control stem placements.

Some florists use a layer of chicken wire on top of fresh flower foam, especially in large-scale arrangements. The added rigidity of the wire layer keeps large stems—such as flowering branches, gladiolus, and protea—in place.

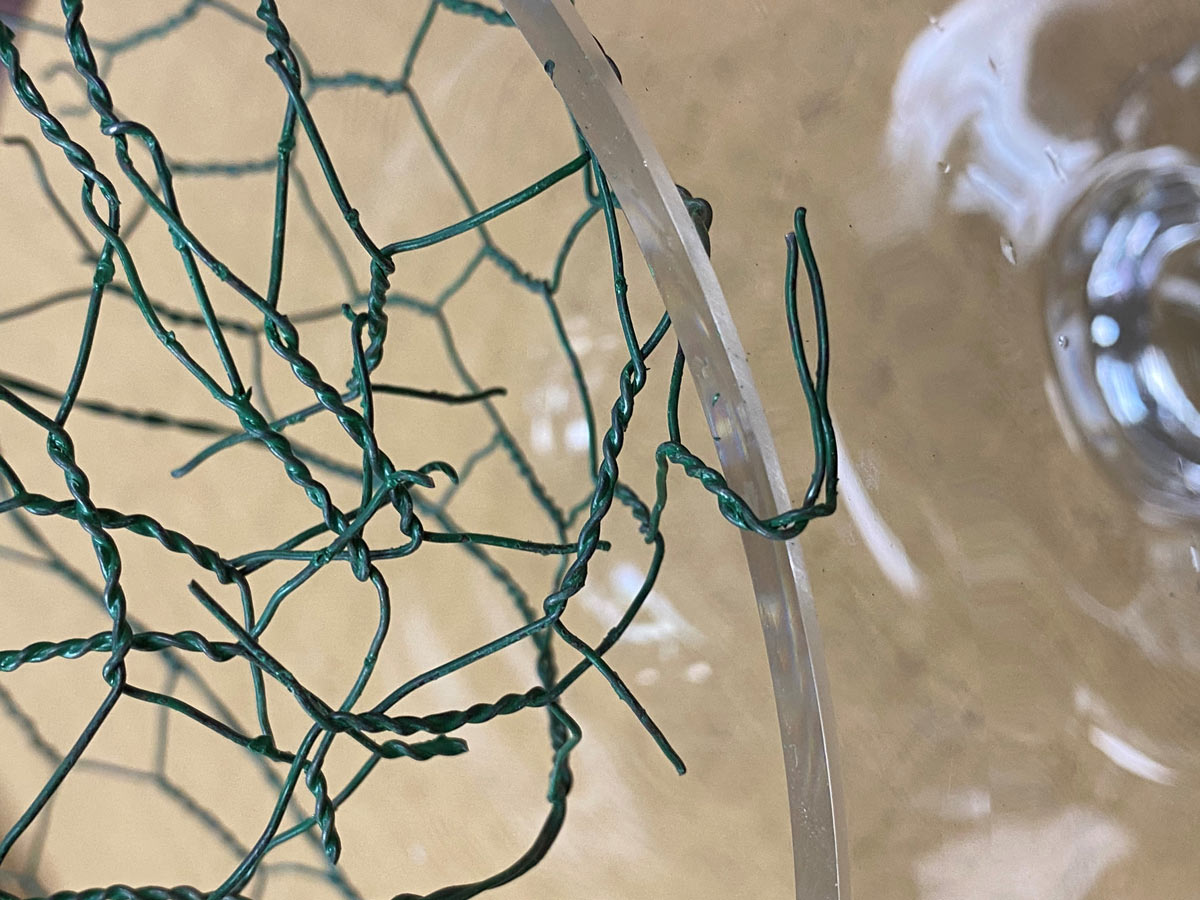

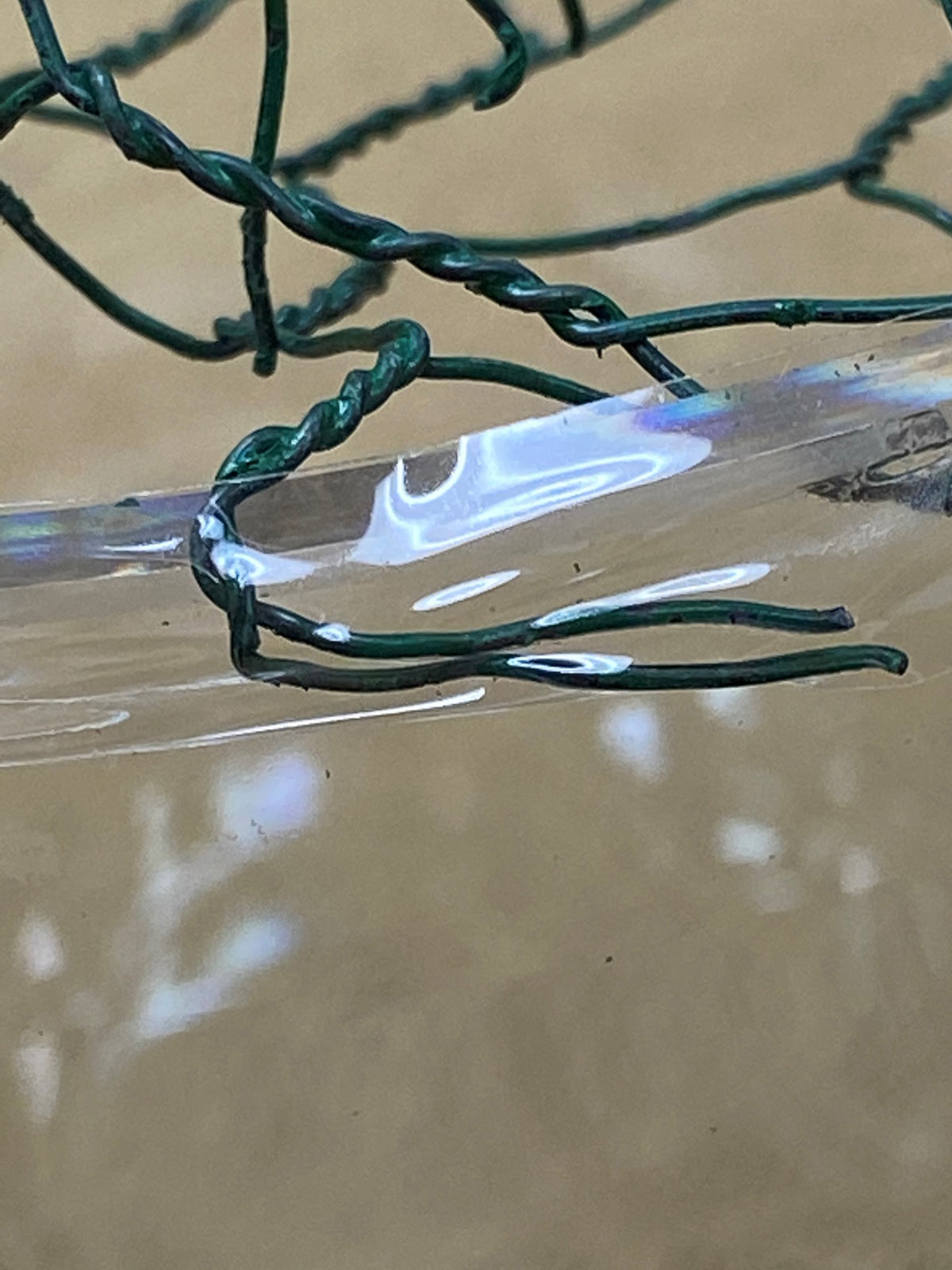

Chicken wire used in floral design is typically 24-gauge wire painted a dark green. This makes it easy to conceal and slows rusting. There are advantages and disadvantages of using chicken wire mechanics.

Chicken wire is inexpensive, depending on the source and quantity purchased. If purchased in bulk, it costs only about 30 cents per foot. Some sources oriented to the craft market may charge much more for smaller quantities. Chicken wire is reusable. While customers don't typically return their containers and mechanics, florists do regularly collect their containers (and associated mechanics) after weddings and events. Because it is metal wire, poultry netting rusts and disintegrates. This feature is attractive to floral designers who want to use eco-friendly products. In addition, it is malleable and can be formed into multiple shapes and sizes.

This mechanic has its downsides, too. Its rust can leave stains that are difficult to remove from glass, crystal, and porcelain. The wire is sharp and can cut, scrape, and puncture your skin. Because the chicken wire is in water, spills are more common than when working with floral foam.

Large Vase Arrangement

For this project, we are creating a floral arrangement suitable for a church altar or a space where the design is against a wall or mirror. All flowers and foliage used in this design were grown in Biloxi and harvested in mid-March. The cut flowers were overwintered in high tunnels.

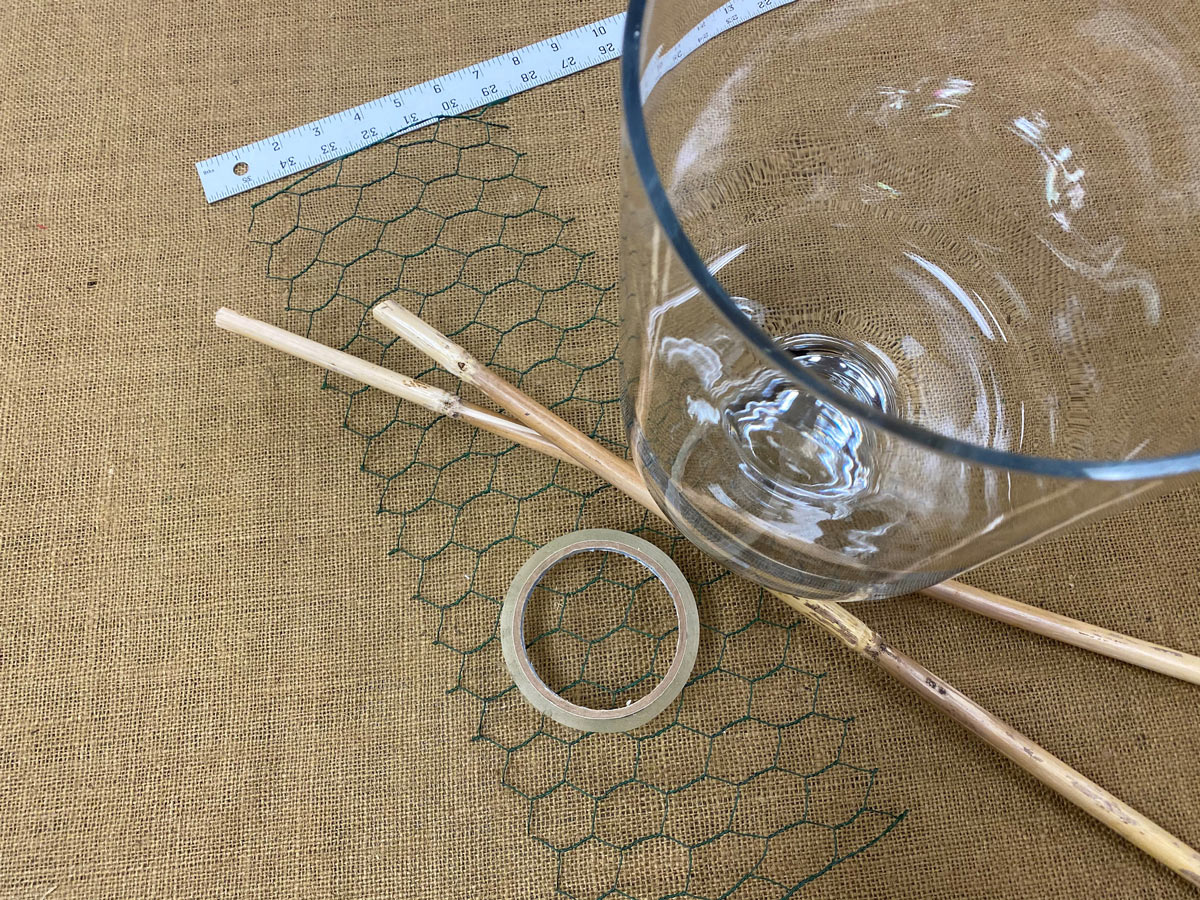

Materials

Chicken wire rectangle, about 6 by 12 inches

Glass vase, about 12 inches diameter by 16 inches tall

Clear waterproof tape

River cane, sturdy stems, dowels, or wooden skewers

Wire cutters, pruning shears, florist knife

Flowers and greenery

- Magnolia grandiflora 'Little Gem', 3 branches

- Elaeagnus pungens, 10 stems

- Dianthus barbatus 'Amazon Neon Rose Magic', 10 stems

- Antirrhinum majus 'Chantilly Yellow' (Chantilly Yellow snapdragon), 20 stems

- Matthiola incana (stock), 10 stems

Fill the vase about three-quarters full with fresh flower food solution formulated for clear glass vase designs. Some flower foods create a cottony precipitate on the bottom of the vase that detracts from the water's clarity, but those labeled for clear vases do not.

The finished arrangement is suitable for a church altar or a space where the design is against a wall or mirror.

For related information, see these MSU Extension publications:

Chicken Wire Mechanics for a Basket Arrangement for the Professional Florist (P3733)

Snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus) for the Farmer Florist (P3301)

Stock (Matthiola incana) for the Farmer Florist (P3252)

References

Butler, S., DelPrince, J., Fowler, C., Gilliam, H., Johnson, J., McKinley, W., Money-Collins, H., Moss, L., Murray, P., Pamper, K., Scace, P., Shelton, F., Verheijen, A., & Whalen, K. (2005). The AIFD guide to floral design. Intelvid.

Dole, J., Stamps, R., Carlson, A., Ahmad, I., & Greer, L. (2017). Postharvest handling of cut flowers and greens (J. Laushman, Ed.). Association of Specialty Cut Flower Growers.

Hunter, N. (2013). The art of floral design (3rd ed.). Delmar.

Wood, M. (2007). The seasonal home. Winward.

Johnson, J., McKinley, W., & Benz, B. (2001). Flowers: Creative design. San Jacinto.

Scace, P. D., & DelPrince, J. (2020). Principles of floral design (2nd ed.). Goodheart-Willcox.

This publication is dedicated to the memory of Mr. Lew Kull, a retail florist in Canton, Ohio. Mr. Kull received professional floristry training through the GI Bill. He purchased a floral shop in 1951 and named it Lew Kull Florists. He recruited the author of this publication, Jim DelPrince, as a store manager and designer in 1983 and taught him the benefits and detriments of chicken wire floral design mechanics, in addition to thousands of other techniques.

The information given here is for educational purposes only. References to commercial products, trade names, or suppliers are made with the understanding that no endorsement is implied and that no discrimination against other products or suppliers is intended.

Publication 3732 (POD-01-22)

By James M. DelPrince, PhD, AIFD, PFCI, Associate Extension Professor, Coastal Mississippi Research and Extension Center.

The Mississippi State University Extension Service is working to ensure all web content is accessible to all users. If you need assistance accessing any of our content, please email the webteam or call 662-325-2262.