Information Possibly Outdated

The information presented on this page was originally released on November 29, 2007. It may not be outdated, but please search our site for more current information. If you plan to quote or reference this information in a publication, please check with the Extension specialist or author before proceeding.

Producers may put fish on insect diet

MISSISSIPPI STATE -- Bugs are just pests for most people, but a group of Mississippi State University scientists is working to make insects an important crop.

Frank Davis, emeritus adjunct professor of entomology, received a phone call in early 2007 from a Florida-based company's president with an interest in mass-producing insects.

“His interest was in mass-producing insects as a sustainable protein source to replace fish meal in fish and livestock feeds,” Davis said

The call brought together a company with diversified interests in seafood and aquaculture technologies with perhaps the only university in the world with the ability to research all aspects of rearing insects as a source of food for fish and other livestock.

Growing insects for use in research began at MSU when the Department of Entomology established a facility called “The Worm Shed” and U.S. Department of Agriculture entomologist R.T. Gast and Davis started growing several insect species on artificial diets in the 1960s at the Boll Weevil Research Laboratory.

As a USDA entomologist for 35 years, Davis led a team that developed a major insect-rearing facility at the federal laboratory for producing pest moth species for corn and cotton research. After retiring, he joined MSU's faculty and organized the university's first Insect Rearing Workshop in the fall of 2000.

The workshop has brought hundreds of scientists from throughout the United States and overseas to campus to learn about raising insects for use in research, for educational purposes and for commercial uses, including natural control of insect pests. The success of the workshop also led to the construction of the Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station's state-of-the-art Insect Rearing Center on campus.

It was the workshop's reputation as one of the few places in the world to learn about rearing insects that caught the attention of Neptune Industries of Boca Raton, Fla.

Ernest Papadoyianis, president of Neptune Industries, said his company was searching for ways to eliminate one of the major bottlenecks in the aquaculture industry -- reliance on fishmeal for protein in fish diets -- when someone mentioned “insects.”

“We had just talked about how many freshwater fish species derive most of their nutrition from various stages of small insects, some just the size of the head of a pin,” he said.

A chance sighting of an industry news article on Davis and the insect-rearing workshop drew the company to MSU.

Aquaculture, the commercial production of seafood in managed ponds or tanks, currently supplies about 46 percent of all seafood consumed in the world today. The United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization predicts that commercially grown supplies will rise to 75 percent of consumption in the next 20 years.

“The supply of wild-caught fish has really been flat since the late 1980s, and those stocks have little chance of regaining their past levels because of pollution, overfishing and other factors affecting commercial fishing,” Papadoyianis said. “Aquaculture is left to bridge the widening gap, and we have to be sustainable in all aspects of our industry.”

More than 25 percent of all fish harvested today are used for fish meal, and the majority of fish meal is used to produce other fish, he said. These baitfish stocks, such as anchovies, menhaden and herring, are exploited, and growing scarcer as time goes on. The result is an ever-tightening supply situation, which has caused sharp price increases over the last year. This trend is expected to worsen.

“For our industry to grow and become independent of protein from wild-caught fish, we have to come up with sources that are sustainable,” Papadoyianis said. “Having a source of high-quality protein that can be mass-produced essentially from processing products such as fruits, grains, vegetables, and even fish and animal waste, would be an ideal situation for the aquaculture industry.”

Just days after the initial telephone call, Papadoyianis and Sal Cherch, Neptune's chief operating officer, visited the MSU campus.

The result of the visit with Davis, entomologist John Schneider, and entomology and plant pathology department head Clarence Collison was an agreement with the university to research the use of feed made from commercially grown insects for fish production.

“The first phase of the research was the selection of insect species with high amounts of protein that can be economically produced by the millions,” Davis said.

By early fall the species were selected and feeding trials began with hybrid striped bass supplied by Neptune.

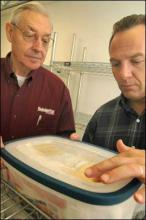

The feeding trials are being conducted by Forest and Wildlife Research Center professor Lou D'Abramo, who is comparing feed pellets made with fish meal to pellets produced from insects. Both were commercially produced and look identical.

“The early trial results indicate the fish have no real preference for one over the other,” D'Abramo said. “In the wild, fish do come to the surface to feed on dragonflies and other insects, so it makes sense that they will eat pellets made from insects.”

D'Abramo is also studying weight gain and other factors that will determine whether the insect-based diet is acceptable for commercial fish production.

The next phase of the research was conducted at MSU's Garrison Sensory Evaluation Laboratory to determine whether an insect diet affects the taste, texture or other qualities of the fish.

“Our evaluation of the samples of hybrid striped bass from the feeding trail indicated no difference in appearance, flavor or texture of the fish grown on the insect-based diet and those grown on the fish meal diet,” said Patti Coggins, director of the sensory evaluation lab. “The only difference we found was that the fillets from the fish raised on the insect diet did not have a strong ‘fishy' smell.”

With research pointing to the potential success of insect-based diets in fish production, Papadoyianis is looking ahead to the next step in the process -- construction of a pilot insect-rearing facility to test growing, harvesting and processing methods.

“We've already had inquiries from all over the world about this,” Papadoyianis said. “Our vision is to have insect production facilities in all of the geographical regions with major commercial aquaculture industries in order to reduce freight costs. That will require researching the use of local insect species, nutrition and production methods, so we envision a long-term relationship with Mississippi State University.”

Contact: Dr. Frank Davis, (662) 325-2983