Information Possibly Outdated

The information presented on this page was originally released on February 2, 2012. It may not be outdated, but please search our site for more current information. If you plan to quote or reference this information in a publication, please check with the Extension specialist or author before proceeding.

MSU researcher finds link to H5N1 bird flu

MISSISSIPPI STATE – A Mississippi State University researcher has uncovered the first molecular evidence linking live poultry markets in China to human H5N1 avian influenza.

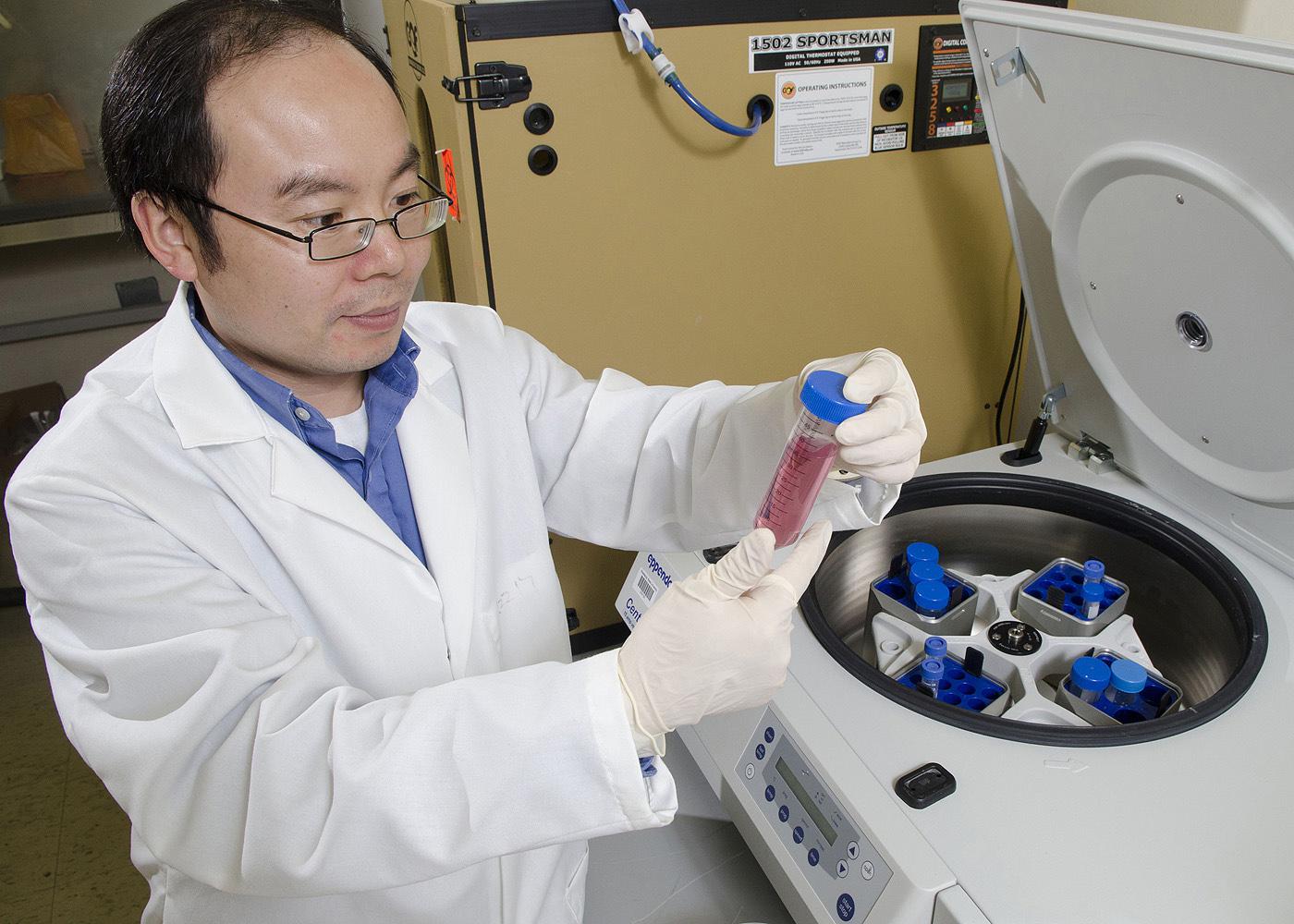

Henry Wan, an assistant professor in systems biology at MSU’s College of Veterinary Medicine, collaborated with scientists in the World Health Organization Collaborative Centers for Influenza in China and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital to investigate the connection.

“Although conceptually we knew live bird markets posed a risk for human H5N1 infection, there had previously not been any direct evidence, especially molecular evidence, supporting this hypothesis,” Wan said.

Based on information provided by patients infected with the H5N1 virus during the 2008-2009 season, Wan and his colleagues collected and analyzed 69 environmental samples from the live bird markets visited by six patients before the onset of the disease.

“From these 69 samples, we isolated a total of 12 highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza viruses from four of the six live bird markets. The similarity of the genetic sequence of the environmental and corresponding human isolates demonstrates a solid link between human infection and live poultry markets,” Wan said.

Wan said the goal of his research is to find the sources of human H5N1 infections and provide the foundations for policy-making for protecting public health. While the United States has regulations in place to protect consumers, this is not the case in all countries.

Wan began studying avian influenza while conducting graduate work in southern China in 1996. He was the first scientist to identify the highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus. One year later, this virus infected humans in Hong Kong, resulting in six deaths.

The subsequent massive depopulation of poultry stopped the human outbreak for a time, but two cases identified in Hong Kong in 2003 confirmed the virus was still circulating in the region and posed a health hazard. From 2003 to 2011, the World Health Organization recorded a total of 566 confirmed human cases for avian influenza worldwide that have resulted in 332 deaths. To date, there have not been any highly pathogenic H5N1 detections in the United States.

Wan, whose other area of expertise is developing computer programs to model the mutation of viruses and to identify vaccine strains, performed an evolutionary study on this virus to identify the links between the human and avian strains of the virus at the molecular level.

“H5N1 viruses have spread to both wild and domestic bird populations in many countries, predominately in Asia, Africa and Europe,” Wan said.

Although no sustained human-to-human transmissions of the H5N1 virus have been confirmed, the mortality rate among human cases to date is about 60 percent.

Wan hopes the results of this study can be used to develop policies to prevent and control H5N1 infections in humans.

“For instance, control and regulations of live bird markets could be used to help prevent the H5N1 human infections in areas that have active live bird markets,” he said.

In the United States, most live bird markets are in major metropolitan areas.

“We have live bird markets in many major cities with large concentrations of ethnic groups who prefer to buy live poultry rather than processed poultry,” said CVM’s Dr. Danny Magee, director of the Poultry Research and Diagnostic Laboratory in Pearl. “The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service has monitoring procedures in place to prevent and control the disease in live bird markets and in the production premises and poultry distributors that supply those markets.”

Magee said Mississippi’s commercial poultry industry follows biosecurity protocols to protect the chickens on the farms from avian influenza.

“Raising chickens in confinement minimizes their exposure to wild migratory waterfowl, which have been identified as possible reservoirs of the avian influenza virus,” he said. “Biosecurity practices also limit exposure of the chickens to unauthorized visitors on the farm. The flocks are raised as securely as possible, and then they are tested for exposure to the avian influenza virus before they are sent to market. Every flock in the state undergoes this serological test so the consumer can be assured that the product is safe.”

Poultry is Mississippi’s top agricultural commodity, with a 2011 production value of $2.21 billion.

“Approximately 15 million broilers are processed in Mississippi each week,” Magee said. “We test the breeders that lay the eggs to produce the broilers, and we test the commercial egg-laying birds. The facility in Pearl is one of the labs in the Southeast that performs the regulatory test to monitor for the presence of the avian influenza virus in the commercial poultry industry.”