Providing Assistance at Calving

Calving season is an exciting, nerve-wracking, and exhausting time of the year for beef producers. Preparation ahead of time will lead to a smoother calving season and healthier calves. A keen eye for emerging problems will also reduce disease spread and the incidence of calf and dam death loss.

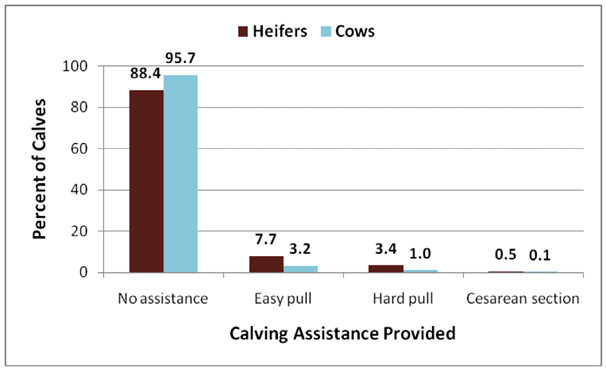

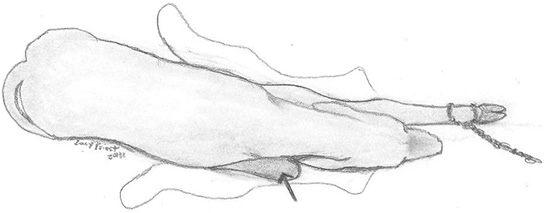

While most calf births proceed unassisted with no complications, some require handler intervention (Figure 1). Heifers are more likely to need assistance than cows. Calf and dam death loss from birth or calving problems is significant. The percentage of calves born alive typically exceeds 95 percent in the Southeast United States and is generally slightly higher in cows than in heifers. Estimates of calf death loss in 2007 show that 25.7 percent of these losses were attributed to birth-related problems in calves less than 3 weeks old. In addition, 2.3 percent of calves aged 3 weeks or older died due to birth-related problems. During this same time period, beef breeding cattle death losses due to calving-related problems was 17.3 percent.

Assistance Provided |

Heifers |

Cows |

|

No assistance |

88.4% |

95.7% |

|

Easy pull |

7.7% |

3.2% |

|

Hard pull |

3.4% |

1.0% |

|

Cesarean section |

0.5% |

0.1% |

Reducing death loss and other calving-related problems starts with close observation of calving females. Ideally, females should be checked at least every 3 hours during calving. Yet only one out of four operations with less than 50 head of cows observed cows during calving three or more times in a 24-hour period. Similarly, only three out of ten of these small operations observed heifers during calving three or more times in a 24-hour period.

Pregnancy Diagnosis

Preparation for the calving season decreases the incidence of morbidity (illness) and mortality (death) in the calves as well as their dams, and it may also improve the postpartum recovery of these cows and heifers and the growth of the calves. One of the best ways to increase preparedness for the calving season is to know which females are pregnant and when they are expected to calve. Performing a pregnancy diagnosis after the breeding season is economically important for various reasons. It also is the most valuable tool to predict which pregnant cattle need increased attention and when they will likely need it.

For example, in a herd of 100 females, a producer knows which 50 became pregnant on the first day of the breeding season from artificial insemination. Using this information, the producer is able to sort out those 50 females so that they can be observed more closely at the start of the calving season. Of the remaining 50 females, the producer knows which of those were bred early versus late, so they can also be observed accordingly. Of course, there are cows, and especially heifers, that may have a shorter gestation as compared to the average of 282 days. Maintaining good breeding records is essential to determine likely calving times. This helps in planning herd observations and improves chances for identifying cattle needing calving assistance.

Stages of Parturition

Understanding the signs and the three stages of parturition (calving) is important in deciding if and when assistance should be given (Table 1). Calving starts with Stage 1, when uterine contractions and cervical dilation occur. The duration of this stage in cattle, on average, is 2–6 hours.

Stage |

Duration |

Events |

|

Stage 1 Preparatory |

2–6 hours |

|

|

Stage 2 Delivery |

30–60 minutes |

|

|

Stage 3 Cleaning |

6–12 hours |

|

Females may isolate themselves from the herd and decrease consumption of feed before they officially begin Stage 1. However, in Stage 1, cattle begin to show indications that they are uncomfortable. Contractions increase in strength and occur closer together, going from 15-minute intervals to once every few minutes. Cattle may frequently lie down and then stand up over and over again. These pregnant females may kick at their underbelly, and a calf hoof may begin to protrude from the vulva. These are all indications that calving is near, and a female should be observed very closely. The water sac, a portion of the placenta, forces through the pelvis, aiding in cervical dilation. This sac often ruptures and hangs from the vulva until calf delivery.

During Stage 2, the fetus enters the birth canal and is expelled. This process may take 30–60 minutes. Heifers often take longer. A delay in reaching Stage 2 is a problem. However, it is not always easy to determine if things are progressing normally or if the cow or heifer is in need of assistance.

The calving female is typically lying down during this process unless restrained in a handling chute. Uterine contractions occur about every 2 minutes and are accompanied by voluntary contractions of the diaphragm and abdominal muscles. Fetal membranes (placenta) and the calf’s forelegs and nose protrude through the vagina. The dam then exerts maximum straining to move the calf’s shoulders and chest through the pelvis. The calf’s hind legs extend backward to allow easier passage through the pelvis. The umbilical cord usually breaks during passage through the vulva, signaling the calf to start breathing. The calf is typically born free of fetal membranes as they remain attached to the dam’s uterus via button attachments between placental cotyledons and uterine caruncles.

Finally, Stage 3 can last 6–12 hours and involves the expulsion of the fetal membranes (“afterbirth”). The cow or heifer will likely stand, begin to clean her calf, and let the calf suckle before Stage 3 is complete. Oxytocin is a hormone produced in the calving female that causes contractions to occur. It is also released in response to suckling. So when the calf begins to suckle, contractions will increase again and assist with the expulsion of the fetal membranes.

Complete removal of the fetal membranes is important so that infection does not occur. A retained placenta is the result of the cervix closing before the entire fetal membranes have been released. Uterine infections can create the need for a longer postpartum interval, delayed rebreeding, and increased medical expenses. Retained placentas should never be manually removed, as lasting damage to the uterus can occur. Consult a veterinarian if placental tissue is still retained 48 hours after parturition. Many factors such as difficult births, stress, disease, genetics, and nutritional causes affect the risk of having a retained placenta. Nutritional factors that increase this risk include energy, protein, vitamin A, vitamin E, selenium, or iodine deficiency during pregnancy.

Difficult Calving

Dystocia, or prolonged and difficult birth, is a leading cause of newborn calf death. It can be the result of a variety of situations. Factors that affect calving difficulty include the following:

- age of dam

- calf’s birth weight

- sex of calf

- dam’s pelvic area

- dam’s body size

- gestation length

- breed of sire

- breed of dam

- sire’s genotype

- dam’s genotype

- nutrition of dam

- condition of dam

- implants and feed additives

- feeding time

- exercise

- uterine environment

- hormonal control

- shape of calf

- position or presentation of fetus

- multiple births

- geographic region

- season of the year

- environmental temperature

- other unknown factors

For example, one of the factors contributing to dystocia is poor nutrition in the dam. This can cause the dam to tire easily during the calving process. In severe cases, the cow or heifer may lack the stamina to expel the calf.

Oftentimes, dystocia is a matter of the pelvic area of the cow or heifer being too narrow relative to the size of the calf. In this situation, either the calf is abnormally large or the pelvis area is abnormally small, causing the calf to have trouble fitting through during the calving process. The pelvic area is wider vertically than horizontally. The widest part of the calf is often the hips. In a tight fit, the calf may need to be rotated so that its pelvis is perpendicular to the dam’s pelvis. In some cases, the calf is shoulder-locked. Turning the calf often allows enough space for it to pass through the birth canal. If twins are present, they may get in each other’s way and block the birth canal, or the dam may tire while delivering the first calf, making delivery of the second calf more difficult.

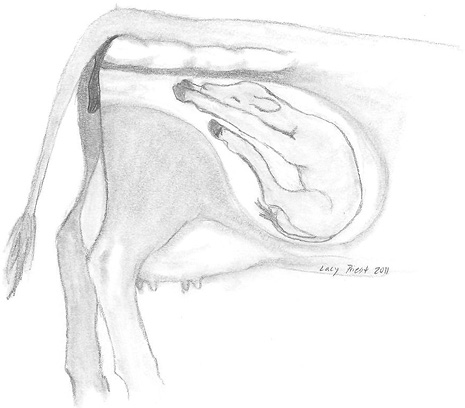

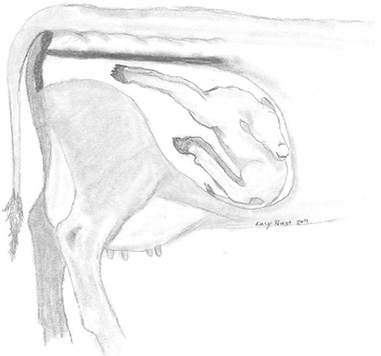

Typically, the fetal calf rotates from being on its back during pregnancy to an upright position with its forelegs and head pointed toward the birth canal. This normal calving presentation consists of the front feet emerging first with the soles of the feet pointing down followed by the calf’s head (as if the calf were diving out of the birth canal) (Figure 2). This presentation provides the least resistance during birth.

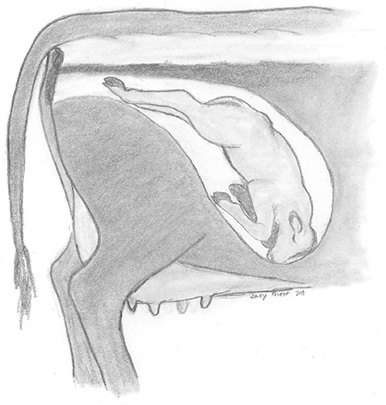

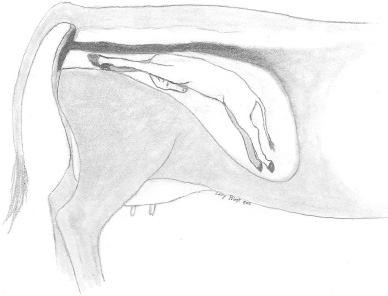

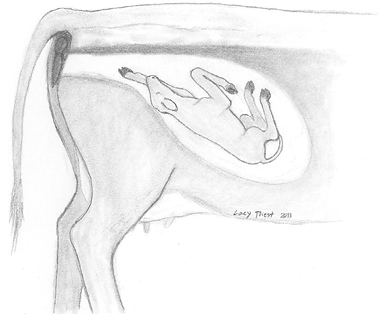

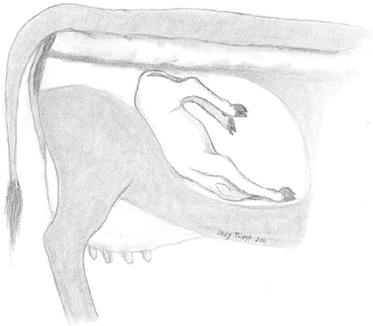

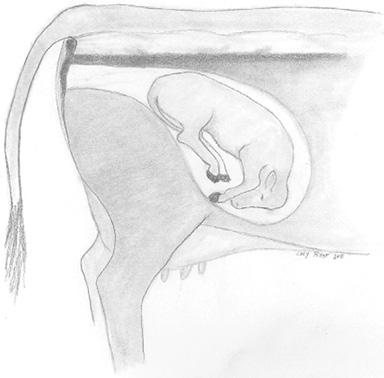

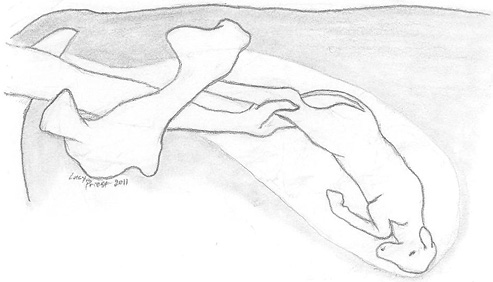

In approximately 30 percent of normal births, the hind legs and tail come first instead of the forelegs and head (Figure 3). Always make sure the tail is protruding with the hind legs in this case. In about 5 percent of births, the calf presents in an abnormal position (Figures 4 to 9). This can lead to dystocia, and assistance may be needed. The goal is to reposition the calf to a normal position to allow for a live birth when possible without damaging the dam’s reproductive tract.

When the head is underneath both forelegs (Figure 4), move the head so that it rests on top of the forelegs for delivery to proceed. Consider all posterior (rear feet first) deliveries as emergencies because the umbilical cord is pinched between the fetus and the pelvis early in the delivery. This slows blood circulation to the fetus and necessitates a rapid delivery.

When the head is turned back or to the side (Figure 5), straighten out the neck and place the head on top of the forelegs for delivery to proceed. Grasp the calf’s mouth or nostrils to pull the head. Do not use excessive force to keep from breaking the calf’s jaw.

In an upside-down presentation (Figures 6 and 7), the best option is often a cesarean section (C-section). Otherwise, attempt to rotate the calf to an upright position. Consider rolling the cow over while keeping the calf in position to accomplish this.

In the breech presentation (Figure 8), the hindquarters are presented first with both hind legs retained. This presentation is very difficult to correct. Push the calf deep into the female with one arm. With the other arm, reach for a hind leg. Straighten out and place both hind legs and the tail in the birth canal for delivery to proceed. Be careful to cover the calf’s hooves during manipulation to keep from damaging the uterus.

One of the most common abnormal presentations is when one or both forelegs are retained and the head is presented in a normal position (Figure 9). In this situation, push the calf back into the female a little ways and use a second arm to reach for the calf’s foreleg. Carefully, straighten out the forelegs so that the head rests on top of them before attempting delivery. Guard the hooves in each hand to protect the uterine wall from damage.

In situations with some abnormal presentations, the only viable option is a C-section performed by a veterinarian. In circumstances where the calf is already dead and cannot be delivered vaginally in one piece, it must be removed in pieces to save the life of the calving female. A wire saw may be needed to accomplish this. To determine if an unborn calf is still alive, try to detect movement by grabbing and pulling on the calf’s tongue or pinching the toes. However, some calves may still be alive and not show any signs of movement.

Dystocia becomes particularly dangerous when predatory animals such as black vultures are near the calving areas. Females having trouble calving or calves slow to stand after birth may be attacked by predators. Many predators seek calving areas in order to consume placentas that have not already been eaten by the cow.

Providing Calving Assistance

Timely calving intervention is critical to save the lives of dams and calves. Cattle that are in labor for too long may give up pushing. This makes it even harder to assist a delivery. Delayed assistance can also have detrimental effects on subsequent calf performance and dam fertility.

Before calving season begins, assemble calving assistance supplies in a readily accessible location. Calving assistance supplies include these:

- Obstetrical (OB) lubricant

- Shoulder-length plastic sleeves

- Disinfectant

- Buckets

- Cloth and paper towels

- OB chains or ropes (chains are easier to disinfect)

- OB handles

- Mechanical calf puller (calf jack, fetal extractor)

- Veterinary contact information

It is typically appropriate to allow a cow or heifer to spend about 2 hours in labor after the water bag appears before intervening in the calving process. Also, if more than 30 minutes elapse without progress, it may be time to intervene. When unsure of how long a female has been in Stage I or II, and especially if one or two hooves are emerging and no progress seems to be happening, it is wise to get a better handle of the situation.

Assisting calving is easiest if the cow or heifer is lying down. However, the female may not stay in a lying position, and even a normally docile female may become aggressive with handlers during calving. If needed, ensure the safety of the female and handlers by restraining her in a squeeze chute to administer assistance. A cattle handling facility with good lighting that allows for ease of cattle movement and restraint is strongly advised. Having calving pastures near cattle handling facilities makes this more convenient and feasible.

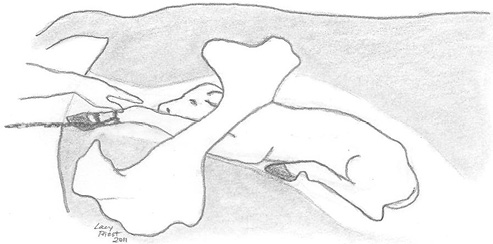

Once the cow or heifer has been secured, preferably in a head lock, put on shoulder-length gloves, use good sanitation and plenty of lubricant to palpate, and determine the position and size of the calf. Palpate the joints (knees versus hocks) in the leg to determine if the front or back legs are emerging first (Figure 10). All four legs have two joints. The joints on the forelegs bend the same direction, whereas the joints on the rear legs bend the opposite direction. If the forelegs are emerging first, feel to determine if both legs are forward and that the head of the calf is between the two legs. The calf may need to be moved to achieve this correct position. Note the direction of the toes as well. If the toes point up, it is most likely that the calf is presenting backward. Only rarely does a calf present head first on its back with the toes pointing up.

Be prepared to contact a veterinarian in the following circumstances:

- The person assisting delivery is unable to determine the position of the calf.

- The correct position cannot be attained.

- The calf is presenting in a posterior position.

- The calf is too large for the birth canal.

- Reasonable progress in the delivery is not made in a timely manner.

- A uterine prolapse occurs.

If the calf is in the correct position and progress is not being made, assistance may have to be given by pulling the calf. Begin pulling by grasping the calf’s legs and pulling on one and then the other, slowly “walking” the calf out using steady traction. Do not jerk the calf or use excessive force. Pulling on one leg at a time will help if the calf is hip-locked. One side of the hip will come through just slightly before the other.

Always pull with the contractions. Do not pull while she is not pushing. If no progress is being made, a producer can use calf chains (Figure 11) or, as a last resort, a mechanical calf puller or “calf jack” (Figure 12). Only an experienced herdsperson or veterinarian should use a calf jack. Never use a vehicle to help pull a calf.

Calving assistance tools have the potential to cause lasting damage to both the calf and the female, so use them cautiously. Never attached OB chains to a calf’s jaw as it will almost always break. Instead, wrap the chain or head snare behind the ears and poll of the head and through the mouth to pull the head (Figure 13).

When attaching a calf OB chain to a leg, make sure that it is done properly (Figure 14). Place one loop tightly around the pastern, the narrowest part of the calf’s leg, and then make a half-hitch and place that loop just below the dewclaw. Then repeat this process with a separate chain on the other leg. The chains should go over the top of the toes to help keep the sharp points of the toes pulled away from the soft tissue of the dam’s reproductive tract. Improper OB chain placement risks breaking the calf’s leg bone (Figure 15). Attach an OB handle to each chain to grip during pulling.

Management after Calving

Once the calf is born, it is important for the dam to bond with her calf. If the dam is in a chute, pull the calf around to the front so she can see, smell, and begin to lick the calf. Stick a piece of straw into the nose of the calf to encourage it to sneeze and clear nasal passages. The calf should stand soon after birth and begin to suckle. It is critical that the calf suckles soon after birth so that colostrum is consumed.

If the dam experienced a difficult calving, be sure to monitor her closely after calving. In the event that she experiences uterine prolapse (an inversion of the uterus), avoid moving her excessively and seek veterinary assistance immediately. This is an emergency situation.

Be prepared to process the calf after calving. Good calving management involves preventing naval infection and moving cow-calf pairs to clean pasture away from calving grounds as appropriate. Keep good calving records including calf birth date, calving ease score, birth weight, dam ID, dam body condition score at calving, and sire ID. Detailed information on calving management appears in Mississippi State University Extension Service Publication 2558 Beef Cattle Calving Management.

Conclusion

Calving seasons are key times for a cow-calf operator. Organization before calving begins can save time and stress for the producer and result in healthier cows and calves. Knowledge about the appropriate time and way to assist in calving is essential on all cow-calf operations. For more information on calving assistance or management, contact your local MSU Extension office.

References

Ritchie, H. D. & P. T. Anderson. 1999. Calving Difficulty in Beef Cattle: Part I. Beef Cattle Handbook. Extension Beef Cattle Resource Committee. Iowa State University. Ames, IA.

National Animal Health Monitoring System – U. S. Department of Agriculture. 2009. BEEF 2007-08. Washington, D.C.

Publication 2675 (POD-08-23)

Reviewed by Brandi Karisch, PhD, Associate Extension/Research Professor, Animal and Dairy Sciences. Written by Jane A. Parish, PhD, Professor and Head, North Mississippi Research and Extension Center, and Jamie E. Larson, PhD, MAFES Associate Director and Professor.

The Mississippi State University Extension Service is working to ensure all web content is accessible to all users. If you need assistance accessing any of our content, please email the webteam or call 662-325-2262.