4-H Livestock Judging Manual

Contents

- Introduction

- Why Judge Livestock?

- Breeds of Livestock

- Livestock Judging

- Basics

- Placing Card

- Class of Livestock

- Livestock Judging Contest

- How to Begin

- Developing a Judging System

- Oral Reasons

- How Good Are Your Oral Reasons?

- Rules for Giving Oral Reasons

- Importance of Accuracy

- Organization of a Set of Reasons

- Sample Notes

- Reasons Format

- Transitions

- Sample Set of Reasons

- Delivering a Set of Oral Reasons

- Terminology for Oral Reasons

- Beef Cattle

- Breeds of Beef Cattle

- Parts of Beef Cattle

- Handling Market Steers

- Beef Cattle Terminology

- Performance Data for Beef Cattle

- Production Situations for Beef Cattle

- Sample Oral Reasons for Beef Cattle

- Junior Yearling Brangus Heifers

- Limousin Heifers

- Market Steers

- Performance Limousin Bulls

- Sheep

- Breeds of Sheep

- Parts of Sheep

- Handling Market Lambs

- Sheep Terminology

- Performance Data for Sheep

- Production Situations for Sheep

- Sample Oral Reasons for Sheep

- Dorset Ewes

- Market Lambs

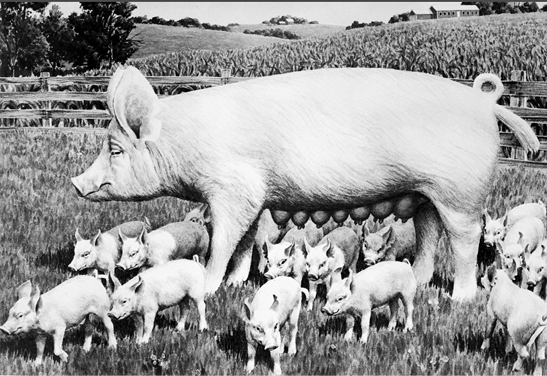

- Swine

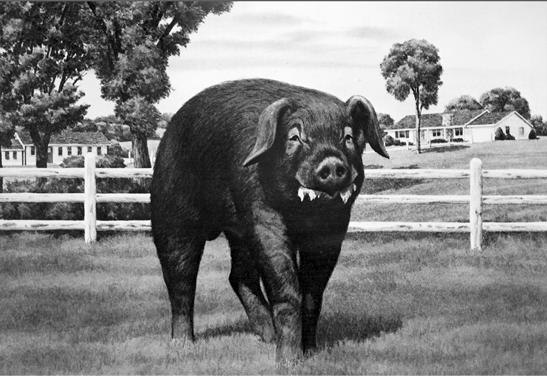

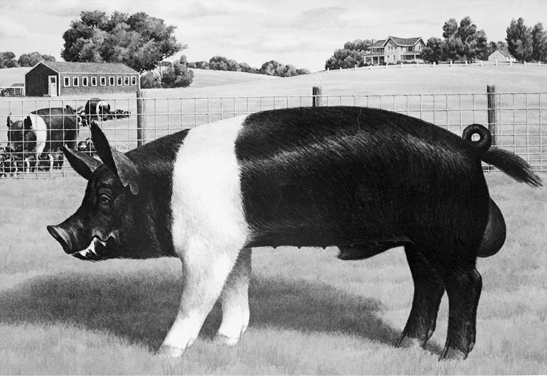

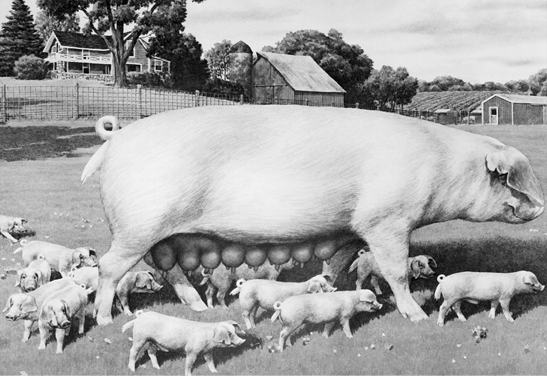

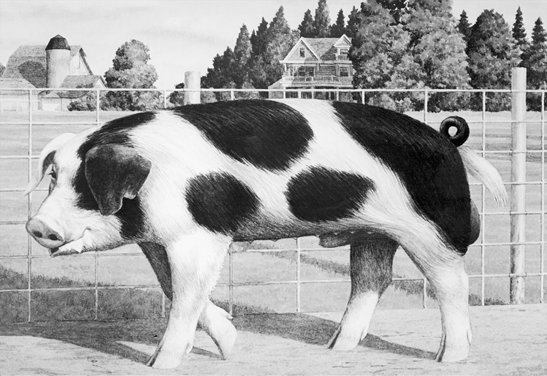

- Breeds of Swine

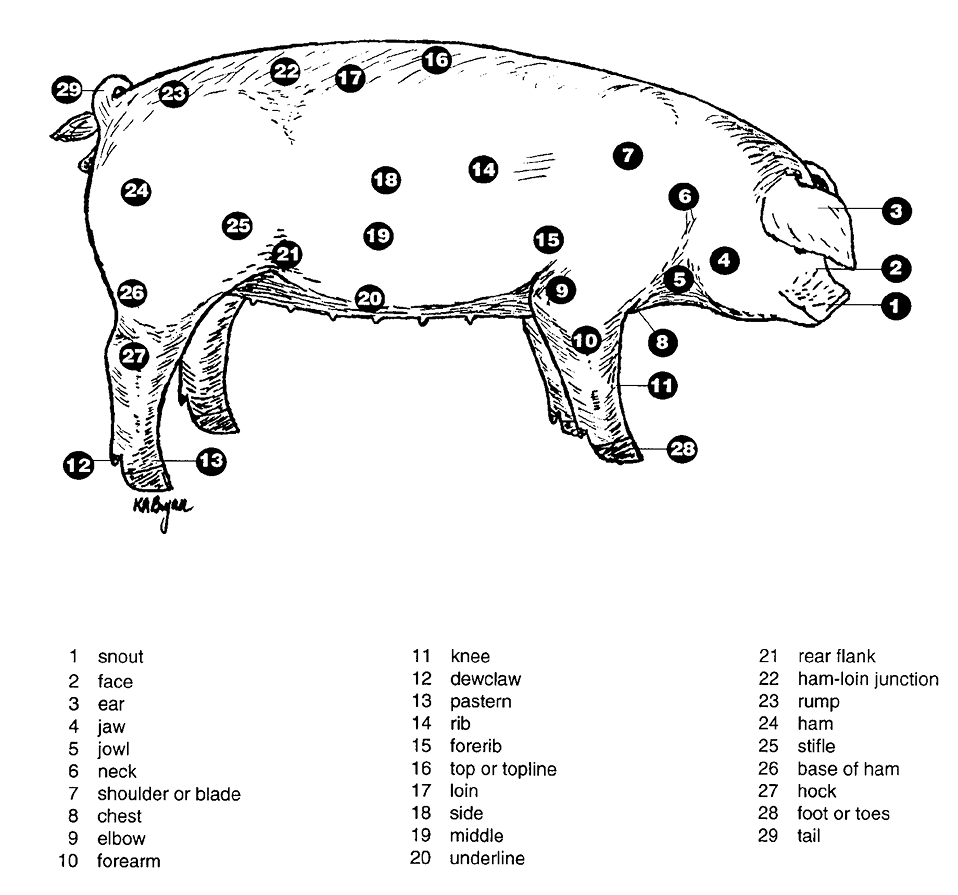

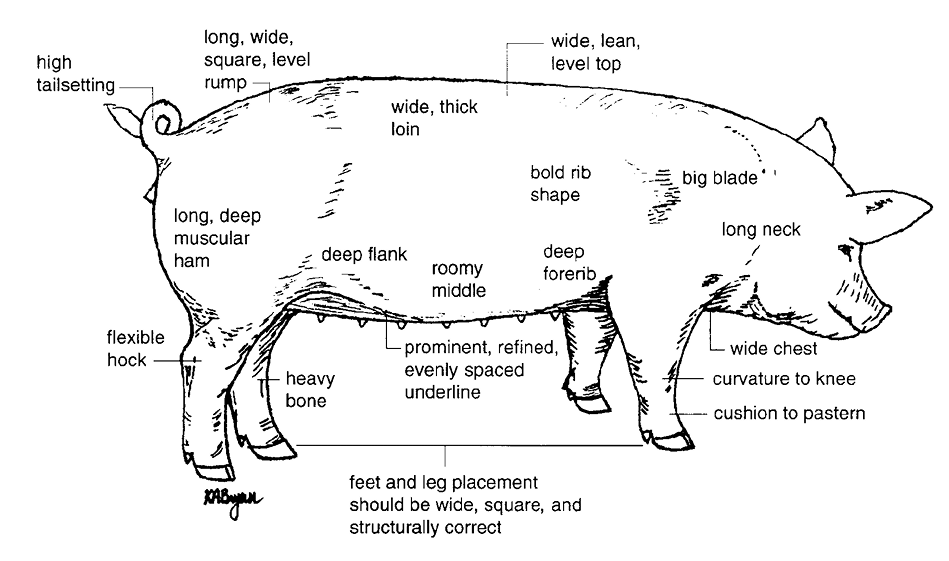

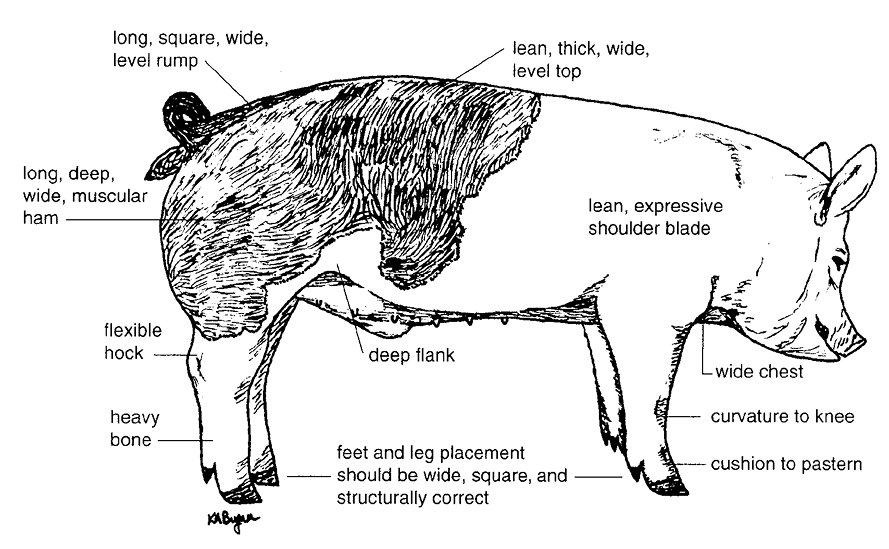

- Parts of Swine

- Swine Terminology

- Performance Data for Swine

- Production Situations for Swine

- Sample Oral Reasons for Swine

- Market Hogs

- Hampshire Gilts

- Glossary

Introduction

Livestock judging is a process of evaluating, selecting, placing, and learning the various livestock species–beef cattle, sheep, and swine. Judging is the foundation of any 4-H livestock project. Feeding, exercising, grooming, and showing the animal are all important aspects of your 4-H project; however, none may be as exciting as selecting your project animal. Selection of project animals is actually judging livestock, comparing the merits of one animal against the merits of other potential project animals. This selection process is just one of many applications of livestock evaluation and judging.

Livestock producers, breeders, feeders, buyers, and packers evaluate livestock for their potential as either breeding or market animals. These people try to relate the “form” of an animal with the “function” for which it is intended to serve. That is why livestock judging is often called the application of “form and function” to livestock.

Why Judge Livestock?

Stockpersons judge livestock to differentiate between superior, average, and inferior animals within each of the livestock industries. They are looking for the most desirable animals for their particular needs. Stockpersons often compare their own livestock to those of others. Using their judging knowledge and skills, producers analyze the potential value of animals for particular purposes.

As a result of reading this manual; listening to your parents, 4-H leaders, and county Extension agents; and practicing on your own, you should be able to do the following:

- Identify the different breeds of livestock

- Compare livestock for their merit and value as either breeding or market animals

- Look at an animal and determine desirable characteristics and faults

- Improve your livestock project by selecting more desirable animals and gain an appreciation of their value for a particular purpose

- Make decisions and defend them in a logical, well-organized manner

- Make complex decisions based on available information

- Develop confidence

- Develop oral communication skills

- Appreciate the opinions of others

Breeds of Livestock

Before learning to compare animals of the same breed, you need knowledge of the most popular breeds. This manual outlines distinguishing characteristics of the major breeds within each species: beef cattle, hogs, and lambs. Use the pictures under each species as a reference.

Livestock Judging

Basics

After learning why livestock are judged, you can begin to appreciate why it takes considerable practice to become a good judge of livestock. In this section, the placing card, a class of livestock, and the livestock judging contest will be discussed.

Placing Card

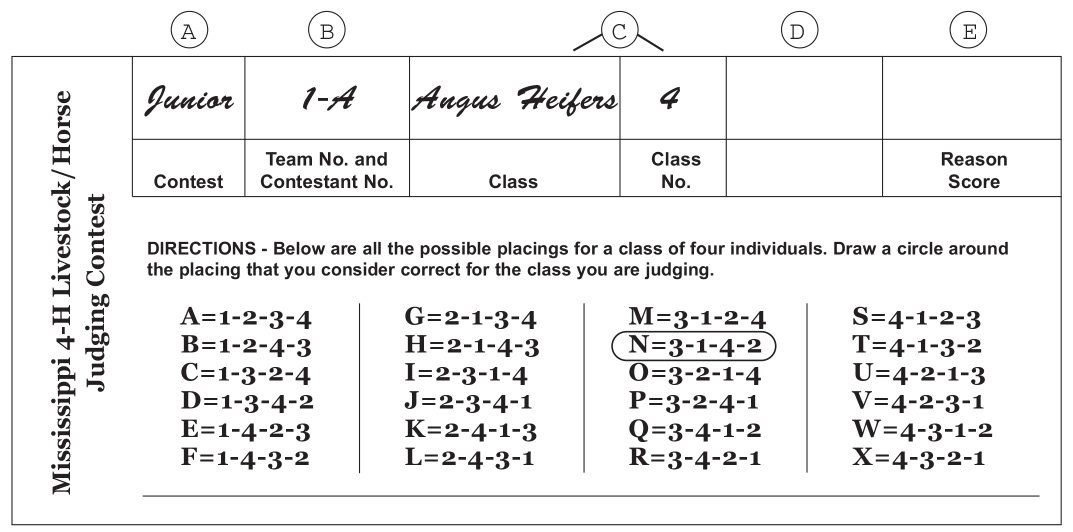

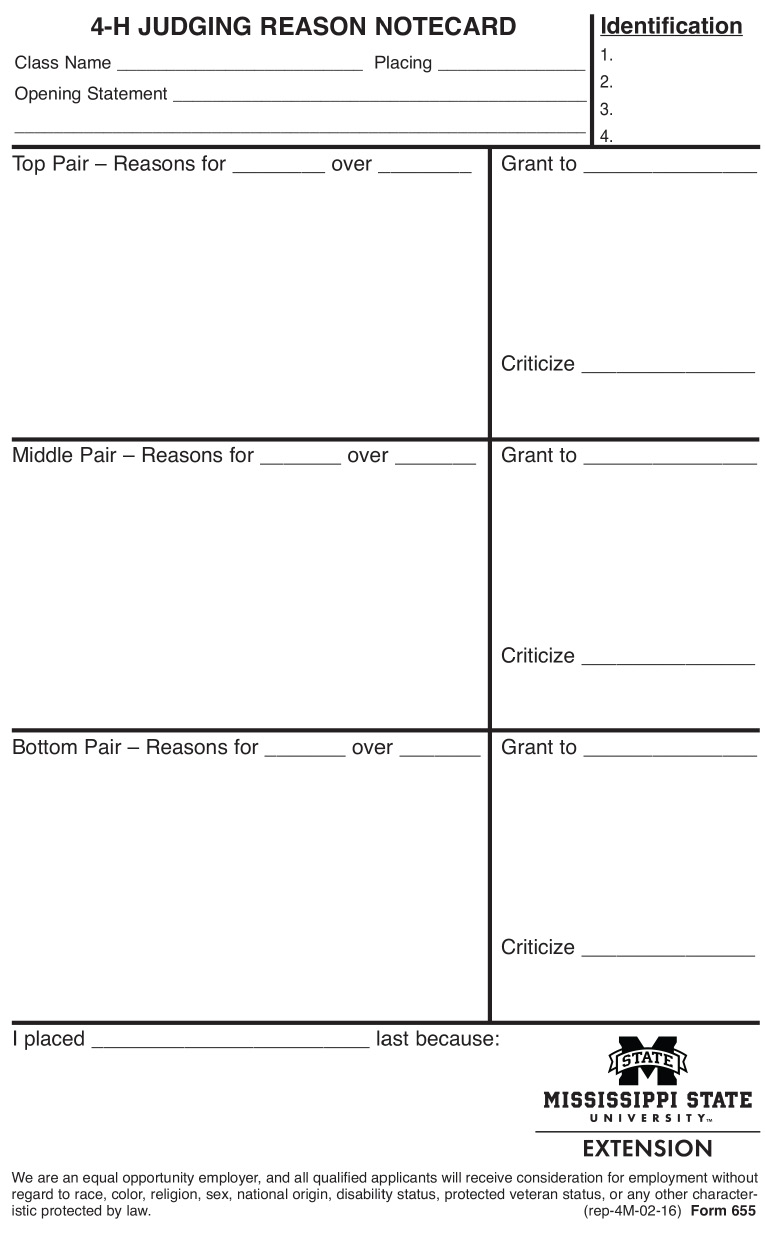

The placing card is the official record of how a person placed a class. Every time you judge a class of livestock, you will be given a placing card. The type of placing cards used in Mississippi contests is shown in Figure 1 (below). Other contests may use similar placing cards. In contest block A, indicate which division you are competing in (most likely, Junior or Senior). Block B is for your team number and contestant number (example 1-A). Block C is for the class name and the class number. Put the name of the class in this block (for example, Angus Heifers). The blocks for D and E are for offical use only and should remain blank. Finally, draw a circle around your desired placing in the bottom section of the card.

In the example, a Junior contestant (1-A) placed Class 4, Angus Heifers, 3-1-4-2. This placing indicates the most desirable animal is number 3 and the least desirable animal is number 2.

Be sure each card you turn in has your contestant number and that you have indicated the name of the class. Circle only one placing on your judging card, and check your placing before turning in your card.

Class of Livestock

A class in a livestock judging contest consists of four animals of one particular breed, sex, and age group, such as Suffolk Yearling Ewes, Dorset Ram Lambs, Crossbred Market Hogs, Duroc Boars, Summer Yearling Hereford Bulls, and Brangus Heifer Calves. The animals will be numbered 1, 2, 3, and 4 so they can be readily identified. Numbers will probably be on the backs or arms of the people holding the animals. A possible exception to this system is when judging beef cattle or sheep and the animals are haltered or are being held in racks. When this is the case, number the animals from left to right as you stand behind them.

Livestock Judging Contest

A livestock judging contest includes classes of beef cattle, sheep, and swine. You may judge either market or breeding classes or both. If you place the class correctly, you will receive a score of 50 points for the placing. If you incorrectly place one or two pairs, or if you make other placing errors, your score will be determined by the seriousness of the error.

In many judging events, you will have the opportunity to give oral reasons. Oral reasons allow you to justify your placings to an official judge. The official judge will score you on accuracy, completeness, length, presentation and delivery, and terminology. A score of 50 points is the highest awarded for oral reasons. Detailed information on reasons can be found in the following “Reasons” section of this manual.

A livestock judging contest is simply a collection of various classes of livestock. There can be as many classes in a contest as the officials desire; usually, there are at least two classes.

Always follow the instructions of your group leader or the person in charge of the contest. If you have any questions, ask your group leader and not another contestant. No talking between contestants is allowed during the contest.

As you approach a class of livestock, you will probably be told to turn your back toward the class and to label your placing card. Do not begin judging until told to do so!

Once “time is in,” begin judging. You will have from 10 to 15 minutes to place a class, with most classes being 15 minutes. With approximately 2 or 3 minutes remaining in a class, you will be asked to mark your card. Make certain that your contestant number, class name and number, and placing are on the card. When “time is out,” turn your back toward the class, check your placing one last time, and hand your placing card to your group leader.

How to Begin

Before you start judging livestock, try to make a mental image of the perfect animal. Do this by recalling the most desirable features of the high-quality animals that you have seen and by thinking of them as belonging to one animal. You can also study pictures of champions, show reports, current livestock magazines, or ideal-type pictures from the breed associations.

In the contest system, four animals are typically in each class. As you judge, divide the class into three pairs: a top pair, a middle pair, and a bottom pair. Make comparisons between these pairs. As you look at any class, have five animals in mind: the four in the class and the ideal animal of that breed, sex, and age group.

Developing a Judging System

Each time you judge a class of livestock or analyze a group of livestock, rely on a system of observing the animals.

Following are a few pointers for judging a class of livestock:

- Stand Back – Allow enough room between yourself and the animals so you can see all four animals at once. Usually, 25 to 30 feet is a good distance from which to view the class. Become skilled in placing the classes from a distance, and handle the animals only to confirm your observations. It is a mistake to place a class only with your hands. An exception is market lambs, which are often placed on visual appraisal as well as on handling.

- Three Angles – Try to look at the class from the side, front, and rear views. Compare each animal to the others in the class and to the “ideal” animal that you have pictured in your mind.

- Big Things First – Always look for and analyze the good and bad characteristics of each animal in the major areas such as frame size, volume, condition, muscling, balance, structural correctness, movement, and breed character. Learn to study the animals carefully. Concentrate on the parts of the animal that yield the high-priced cuts. A keen judge of livestock is orderly and is never haphazard. Make your placings according to the big things, unless a pair of animals are very similar, causing you to analyze the minor differences between the animals.

- Place the Class – Once you have analyzed the important factors that go into placing a class, place the class. Mark your placing at the top of your notebook or reasons card, and begin taking notes. A more thorough discussion of note taking and reasons format is in the “Oral Reasons” section of this manual.

- Close Inspection – Usually, you will be given some time for close inspection of a class. When you are near the animals for close inspection or handling, simply confirm the decisions you made at a distance. If an animal appears different (or handles differently) from what it looked like from a distance and if the difference merits consideration, then change your placing. Close inspection is different for each species, so they will be dealt with separately.

Beef Cattle – During close inspection of beef cattle, you probably will not be permitted to handle breeding animals, but you may be allowed to handle animals in a market class. If you are permitted to handle the animals, move quietly and cautiously so you don’t excite or frighten the animals (See “Handling Market Steers”).

Sheep – During close inspection of sheep, you may or may not be permitted to handle breeding and market classes. Again, move quietly and cautiously so the animals do not become nervous or excited. A section in this manual deals with the preferred method of handling sheep (See “Handling Market Lambs”).

Swine – There are no predetermined guidelines for close inspection of swine because hogs are usually judged loose in a pen. At any time during the class, you may kneel and look at underlines, ear notches, or feet and legs. Make this part of your normal routine for judging pigs.

Stand Back and Take Notes – Even if it is not a reasons or questions class, write down a few notes on why you placed the class the way you did. If it is a reasons class or a class with questions, stand back from the class and write your notes for reasons. If you are unsure of something, either try to look at it again or omit it. If you are unsure and guess, you will probably be wrong. Try to be accurate and descriptive when writing notes, and remember what the animals look like.

Oral Reasons

Good judges of livestock have a special quality that an average judge does not possess. A good judge can accurately and concisely describe an animal or group of animals so that an audience knows exactly what the judge saw. The ability to describe animals accurately and concisely is the basic foundation of the reasons process. This section is devoted to reasons, starting with the basics and ending with a lengthy list of terminology.

- Giving reasons will help you do the following:

- Develop a system for analyzing a class of livestock

- Think more clearly on your feet

- Organize and state your thoughts more clearly

- Improve your speaking poise and presentation

- Improve your voice

- Develop your memory

You should know the parts of the various livestock species and how they join to make a particular breeding or market animal. Every animal is different and so is every class of livestock. Therefore, there are no guidelines or rules for placing a class. Nor is there a right way or a wrong way to deliver or present a set of reasons.

How Good Are Your Oral Reasons?

The judge will determine the value of your reasons by the following:

- Accuracy – You must tell the truth. You must see the important things in the class correctly. Accuracy is very important. You will lose points for incorrect statements.

- Completeness – Describe all the major differences in your reasons. Omit small things that leave room for doubt.

- Length – A well-organized, properly delivered set of reasons must never be more than 2 minutes in length.

- Presentation and Delivery – Present your reasons in a logical manner that is pleasant to hear, is clear, and is easy to follow. If reasons are poorly presented, the value of accuracy may be lost because most of what you say doesn’t “get through” to the listener. Speak slowly and clearly in a conversational tone. Speak loudly enough to be understood, but avoid talking too loudly or too rapidly. Use well-organized statements and use correct grammar. Emphasize the important comparisons and be confident in your presentation.

- Terminology – Use correct terminology. Incorrect terminology greatly detracts from the value of your reasons. Study and use the terms in this guide (See “Terminology for Oral Reasons”).

Rules for Giving Oral Reasons

- Do not claim strong points for one animal unless the animal has them. Claim the points when one is superior, and then grant to the other animal its points of advantage.

- Strongly emphasize major differences. Present the important differences first on each pair.

- Be concise and definite. Don’t search for things to say. If you don’t remember, go on to the next pair you are to discuss.

- State your reasons with confidence and without hesitation. Talk with enough vim and vigor to keep the judge interested, but do not yell or shout.

- End reasons strongly. Give a concise and final statement on why you placed the fourth-placed animal last.

- Be sure you have your reasons well organized so you do not hesitate when you present them to the judge.

The most important factors that go into an effective set of reasons include the following:

- Accuracy

- Organization

- Delivery

- Terminology

Let’s review these factors to improve your set of reasons.

Importance of Accuracy

Accuracy is the most important aspect of a good set of reasons. Not only must you be able to see important differences among animals, but you must be able to describe these differences accurately. Two animals may be extremely similar except for one or two minor differences, or they may be extremely different and have very little in common. In your reasons, you must be able to identify the important differences and similarities among animals and convey these traits to the judge. The official judge will want you to paint a picture of the animals by using the proper terminology to describe the animals.

Correct phrases about the livestock are the foundation of accuracy. Claim strong points for an animal only if the animal has them. Do not try to make small differences into big placing points. Furthermore, do not try to impress the judge with a discussion of every point that is different among animals. Discuss only the most important reasons for placing one animal above another.

Organization of a Set of Reasons

Organization is the second important factor that should be a part of your reasons. It is easier for the person listening to you to understand what you are saying if you present things in a logical, well-ordered fashion. This organization begins with taking notes. If your notes are organized, your reasons will be organized also.

In your reasons, divide a class into three pairs: a top pair, a middle pair, and a bottom pair. Your notes for reasons also should be divided into three pairs.

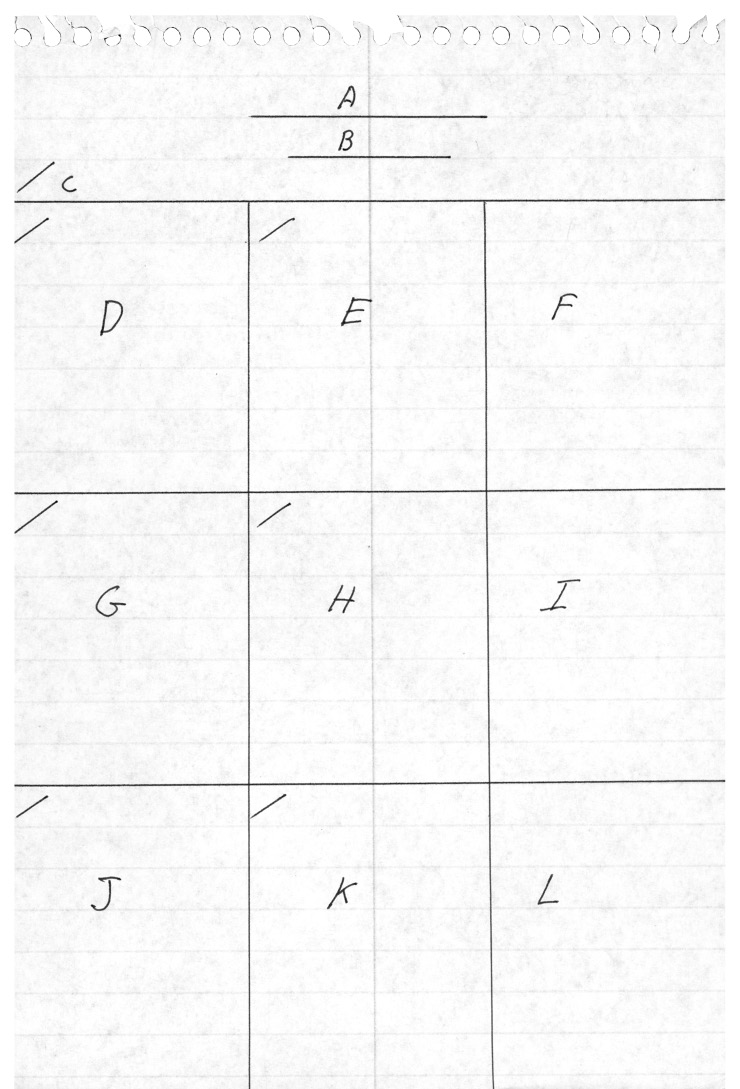

When taking notes, use either the 4-H Judging Reasons Notecard or a notebook, both of which will be described in this section.

You may use the Reasons Notecard or a notebook in the same manner as shown in Figures 2 and 3. However, the notecard may be easier for beginners and juniors. Line A is used for class name and Line B is for class placing. Section C refers to the opening statement for the class. Boxes D, E, and F refer to the top pair; boxes G, H, and I refer to the middle pair; and J, K, and L refer to the bottom pair. Boxes D, G, and J are for placings; boxes E, H, and K are for grants; and boxes F, I, and L are for faults or criticisms. This outline for note taking can be used for any class of four animals with any placing.

Sample Notes

When you begin taking notes, always write down the most obvious characteristics first, then underneath the big things, write the details or specific differences.

Reasons Format

The format used for reasons is simple and straightforward and allows for a complete description of a class. This style does require an understanding of livestock evaluation as animals are analyzed in great detail, and one must have the ability to recognize important differences and to place these differences in a priority order.

Following is an outline that demonstrates the basic format:

Opening statement: Selecting the most . . ., I chose the alignment of 1-2-3-4 for the (name of class).

Criticism of top animal: I realize that 1 could be . . . .

Comparison of 1 over 2: Nevertheless, I used 1 over 2 in the top pair as he was . . . .

Grants 2 over 1: Sure, 2 was . . . .

Criticism of 2: but, the Duroc barrow is . . ., so he is second.

Comparison of 2 over 3: However, with these faults aside, it is the . . . of 2 over the . . . of 3.

Grants 3 over 2: I recognize that 3 is . . . .

Criticism of 3: but at the same time, he is . . . .

Comparison of 3 over 4: Even so, in my concluding pair, 3 beats 4. He is a more . . . .

Grant 4 over 3: I realize 4 is . . . .

Criticism of 4: However, this does not make up for the fact . . . .

The type of terminology used in each section of the reasons is important. In the opening statement on the top animal, you may use either descriptive terms or class comparisons. In the pair comparisons, you may use either class comparisons (. . .est) or simple comparative (. . .er) terms. Grants are comparative terms or class comparisons. Criticisms are descriptive (no “er” terms) or class comparisons.

Properly used, this format will allow you to completely describe all of the important points in a class in a well-organized, easy-to-follow manner.

Transitions

Transitions are a way of moving smoothly from one section of the reasons to another. This is done as simply as possible while still maintaining a smooth transition. We strongly discourage excessively wordy transition statements.

Listed below are words to use when moving into a grant:

- Grant

- Recognize

- Realize

- Concede

- Admit

- Yes

You may want to try something such as this statement: “2 is straighter lined and cleaner fronted, but he is . . .” (move into criticism). Here we are using only “but” for the transition term, but effective voice inflection is necessary to make this work.

To move into a criticism, use the following language:

- I realize that 1 is . . .; nevertheless, I used him in the top pair over 2 as he was . . . .

- But he is the lightest muscled, barest handling . . . .

- But I criticized 2 and left him second, as he was . . . .

- But I faulted 2 and placed him second, as he was . . . .

When moving into another pair, here are some transitions that can be used:

- Still, in the bottom pair, I used 3 over 4.

- Nonetheless, in the top pair of heavier muscled gilts, it’s 1 over 2.

- Nevertheless, in the middle pair, I used 2 over 3.

- Even so, in the bottom pair . . . .

- However, in the middle pair . . . .

Just a brief word about originality: Experiment with different transitions and phrasings. Try them on the coach, and if he or she doesn’t like them, you will be the first to know. Note to the juniors: Get the basics down first, then start finding original ways to say things.

Sample Set of Reasons

“I placed the Angus Heifers 3-1-4-2.

I started the class with 3, the heaviest muscled, highest volumed, growthiest heifer in the class. Ideally, I would like to see her longer necked and smoother shouldered! Even so, I used 3 over 1, as she was a larger framed, heavier muscled, bigger volumed, growthier heifer. She was a longer bodied, taller topped heifer that has more arch and spring of rib, with more width and natural thickness down her top and through all portions of her quarter. In addition, she appeared to have a higher weight per day of age. However, I do admit that 1 was a more feminine-fronted heifer, being more refined about her head, longer necked, and laid in smoother about her shoulder, but she was a shallower ribbed, lighter muscled heifer that is pinched in her forerib.

Coming to my middle pair, I placed 1 over 4 because she was a more feminine, longer bodied, and more structurally correct heifer. She was especially smoother through her neck/shoulder junction, longer sided, and stood more squarely on her feet and legs. Granted, 4 was a heavier muscled, more ruggedly designed heifer that stood on more substance of bone, but I criticized her for being a more conventional, coarser shouldered heifer that was cow hocked and splay footed.

Dropping to my bottom pair, I placed 4 over 2 as she was a heavier, bigger volumed, heavier muscled heifer that stood on a greater diameter of bone. She had more arch and spring through a deeper rib, with more thickness down her top and a greater volume of muscle from hip to hock. However, 2 was a more feminine, leaner about her neck, and smoother shouldered. Nonetheless, 2 was the smallest framed, lightest muscled, narrowest made heifer in the class and stood on the finest bone with the lowest weight per day of age. Thank you.”

Delivering a Set of Oral Reasons

Delivery is the third factor that is necessary for a good set of reasons. Everyone is nervous the first time he or she gives a set of reasons, but with practice, it will become easier. These six factors for delivering a good set of reasons will help you:

- Flow – The way you put words together into phrases, sentences, and paragraphs is considered flow. A group of short, choppy phrases, each standing alone, is boring and difficult to follow. A group of long, smooth-flowing phrases is enjoyable for the listener. Begin your reasons at one speed and keep a similar pace throughout the entire set. Don’t talk too quickly or too slowly. Speaking without hesitation will allow you to receive a higher score for your reasons. The only times to pause are between pairs and when you need to take a breath. Follow every set of reasons with a sincere “Thank you.”

- Inflection – Voice inflection is one of the most important items in your delivery. Place emphasis on the words that describe the important characteristics of each animal. Careful selection of key words to emphasize will take some practice, but in time, it should become a normal part of your oral reasons.

- Volume – The volume you use to deliver your reasons will depend on how you normally speak and the size of the room. If you are soft spoken and are in a large room, increase the volume of your voice in order to be heard and understood clearly. If you are normally loud and are giving reasons in a small room, decrease the volume of your voice so it doesn’t echo.

- Eye Contact – Try to look at the person who is listening to your reasons. If you maintain eye contact throughout the entire set, your reasons will be more professional. Direct your discussion toward the official even if you do not look the judge straight in the eye. It is easier for some people to look at the top of the judge’s head when giving reasons rather than looking him or her directly in the eye. You will receive a higher score if you do not gaze into space or look around the room.

- Distance – Depending on your voice and stature, the distance you stand from the judge will vary. A short, soft-spoken person should stand closer to the judge than a tall, deep-voiced person whose voice carries well. Nonetheless, 6 to 10 feet is generally adequate.

- Stance – When giving a set of reasons, make the situation as comfortable as possible for the judge and for yourself. Stand upright, with your hands behind your back or folded at your waist. Place your feet squarely at shoulders’ width. Avoid rocking back and forth or rolling on the balls of your feet.

Terminology for Oral Reasons

Terminology is the fourth and final factor that goes into an effective set of reasons. Try to put the words and phrases together in a well-organized, logical fashion when describing livestock. Be sure to describe only what you see, and never invent things that are not there.

It is important to know the meaning of every term or phrase you use. An official who is unfamiliar with a certain term may ask you to define it further. As you look over the terms, try to picture an animal with the characteristics described by the terms, or terminology. If you are uncertain about the exact meaning of a term or phrase, ask your parents, 4-H leader, or Extension agent.

More desirable and less desirable characteristics are listed on the terminology pages for several traits of each species (beef, swine, sheep). Use caution when applying the terminology in a set of reasons; in some instances, a desirable characteristic in one situation may actually be an undesirable characteristic in another (for example, larger framed versus smaller framed). Furthermore, not every term in the lists has an appropriate opposite term; if there is no term, it is shown as ————. For terms that contain a blank (_____), insert the appropriate part of the animal you are describing.

Beef Cattle

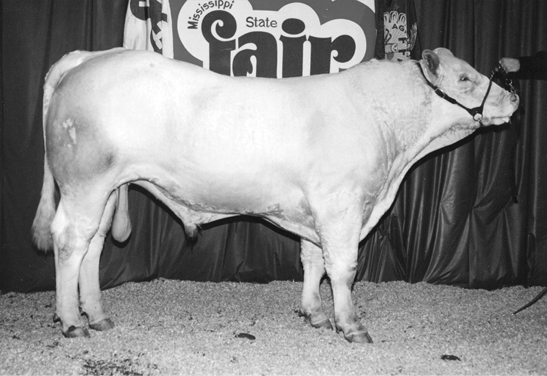

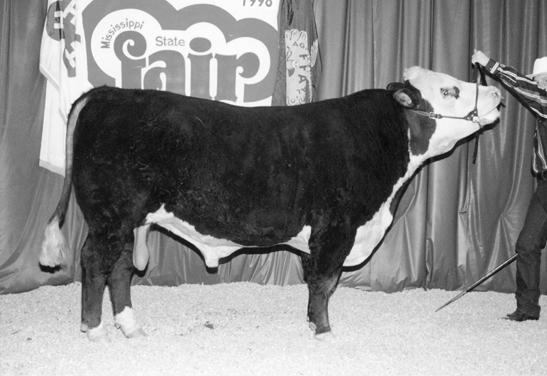

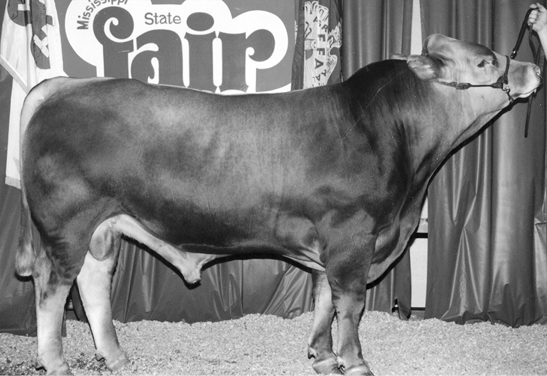

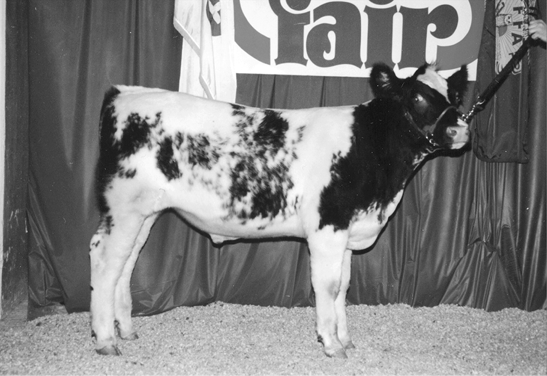

Breeds of Beef Cattle

Table 1 outlines some breeds of beef cattle that are common in the United States. Each breed is categorized by frame size, muscling, mature cow weight, milking ability, and some of the more distinguishing features of the breed.

Frame size is divided into three categories: small, average, and large. Muscle is divided into three categories: flat, medium, and thick. Average mature cow weight is listed in pounds and describes the size of cows of this breed relative to other breeds.

It is important to remember that this table is for reference only. As much variation exists within a particular breed of livestock as among breeds for such characteristics as milking ability, muscle, and so on. Therefore, the data contained in this table represent averages, not absolute values, for particular breeds. The table is provided as a reference to help you better distinguish one breed from another.

|

Breed |

Frame size |

Muscle |

Avg. cow wt. |

Birth wt.a |

Wean wt.a |

Post-wean wt.a |

Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Angus |

avg. |

med. |

1,100 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

black; polled; pigment; fertility |

|

Beefalo |

small |

med. |

varies |

—— |

—— |

—— |

brown; 3/8 Buffalo, 5/8 Bovine |

|

Beefmaster |

avg. |

med. |

varies |

4 |

2 |

2 |

1/2 Brahman, 1/4 Hereford, 1/4 Shorthorn |

|

Blonde d’Aquitaine |

large |

thick |

1,500 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

blonde; terminal sire |

|

Braford |

avg. |

med. |

1,250 |

—— |

—— |

—— |

reddish; 3/8 Brahman, 5/8 Hereford |

|

Brahman Brangus |

avg. avg. |

med. med. |

1,400 1,250 |

4 3 |

1 3 |

3 3 |

various colors; heat tolerance; “hump” black or red; 3/8 Brahman, 5/8 Angus |

|

Charbray Charolais |

large large |

med. thick |

1,500 1,550 |

—— 5 |

—— 1 |

—— 1 |

whitish gray; 3/8 Brahman, 3/8 Charolais white; muscle; growth |

|

Chianina |

large |

med. |

1,600 |

5 |

1 |

1 |

white, silver, brindle, or black; terminal sire |

|

Devon |

small |

flat |

1,100 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

dark red; carcass quality |

|

Galloway |

small |

flat |

950 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

black; long, curly hair; late maturing |

|

Gelbvieh |

avg. |

thick |

1,450 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

pale brownish-orange; milk; growth |

|

Hereford |

avg. |

med. |

1,100 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

red with white face; adaptability; fertility |

|

Limousin |

avg. |

thick |

1,300 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

pale brown, golden; muscle; cutability |

|

Longhorn |

small |

flat |

varies |

1 |

5 |

5 |

various colors; late maturing; long, slender horns |

|

Maine-Anjou |

large |

thick |

1,600 |

5 |

1 |

1 |

deep red and white; frame; growth rate; muscle |

|

Marchigiana |

large |

thick |

1,500 |

—— |

—— |

—— |

grayish-white; muscle; terminal sire |

|

Murray Grey |

small |

med. |

1,150 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

gray; low birth weights |

|

Pinzgauer |

avg. |

thick |

1,350 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

brown with white topline, underline; hardiness |

|

Red Angus |

avg. |

med. |

1,100 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

red; polled; fertility |

|

Salers |

avg. |

med. |

1,300 |

—— |

—— |

—— |

dark red or black; low birth weight; growth |

|

Santa Gertrudis |

large |

med. |

1,450 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

deep red; 3/8 Brahman, 5/8 Shorthorn |

|

Scotch Highland |

small |

flat |

900 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

dun; long, dense, shaggy hair |

|

Shorthorn |

avg. |

med. |

1,100 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

red, roan, or white; calving ease; early maturing |

|

Simmental |

large |

thick |

1,500 |

5 |

1 |

1 |

red, cream, or black with white; muscle; milk |

|

South Devon |

large |

flat |

1,450 |

—— |

—— |

—— |

light red; milk; growth rate |

aRanking based on 1 (most desirable) through 5 (least desirable). Insufficient data for comparison are indicated by ——.

Adapted from Beef Production and Management, 2nd edition, 1979, Gary L Minish and Danny G. Fox.

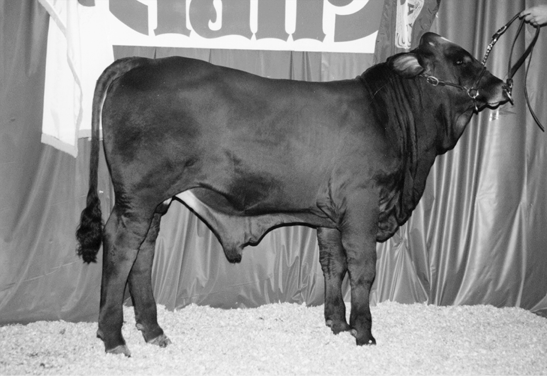

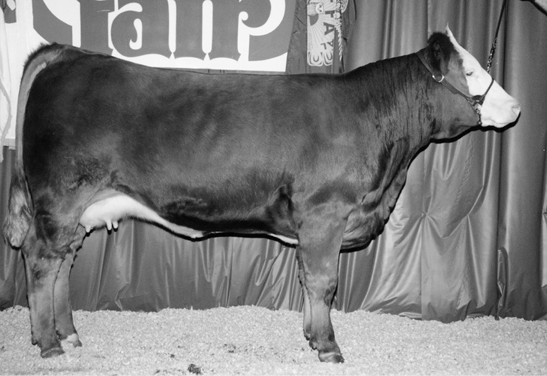

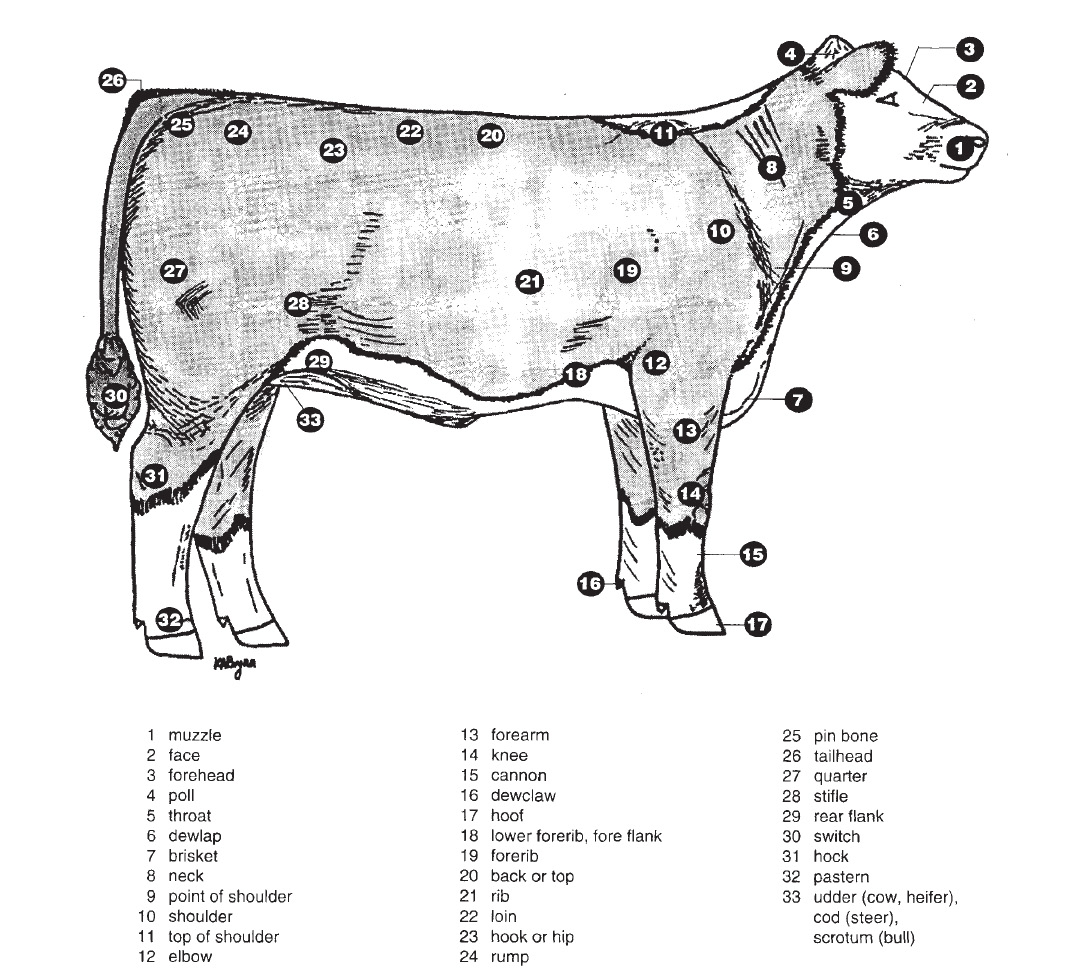

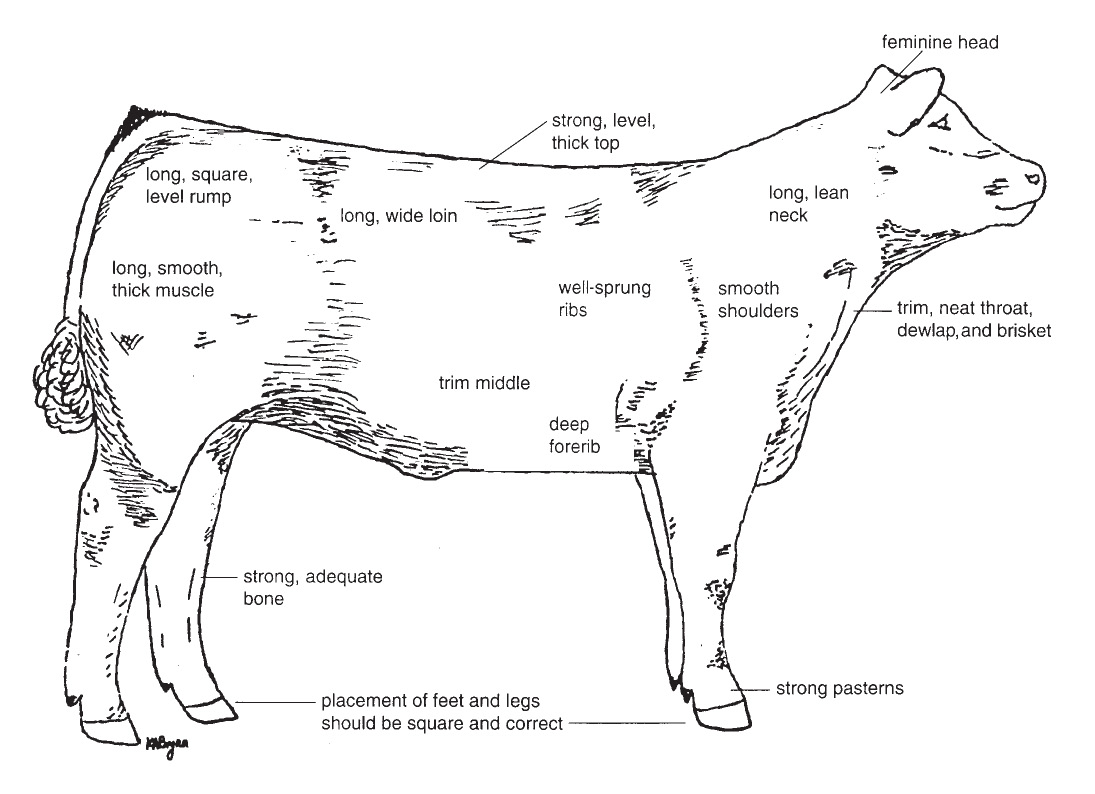

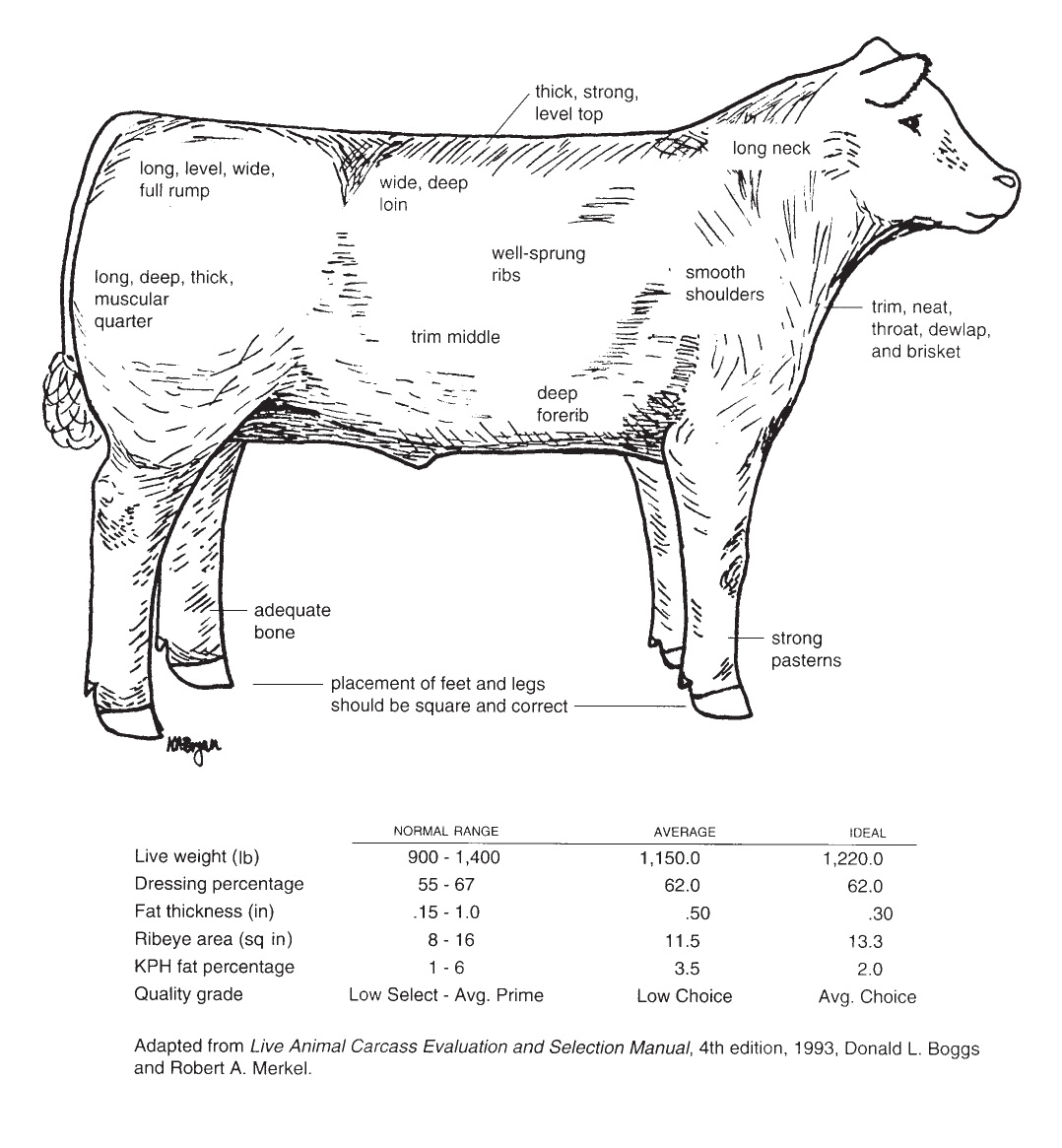

Parts of Beef Cattle

After you have become familiar with the breeds of beef cattle, learn the external parts and carcass regions. This section provides diagrams of the external parts (Figure 4), characteristics of an ideal breeding heifer (Figure 5), and characteristics of an ideal market steer (Figure 6). Take time to study all of the parts and to become familiar with them so you can refer to them without hesitation. Use these terms as part of your reasons.

Characteristics of the ideal breeding heifer and the ideal market steer are included for reference only. Depending on the location and production situation, an ideal can take on various shapes and forms.

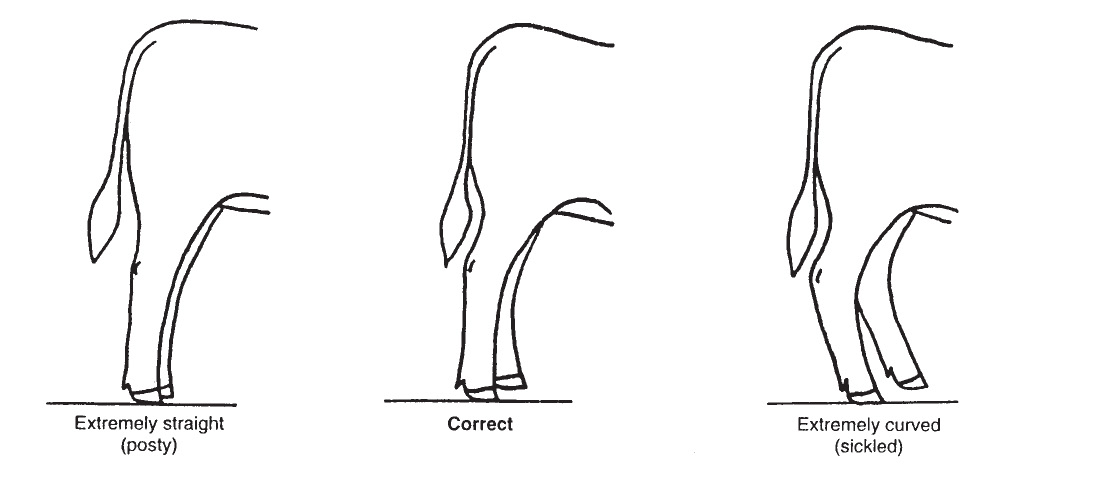

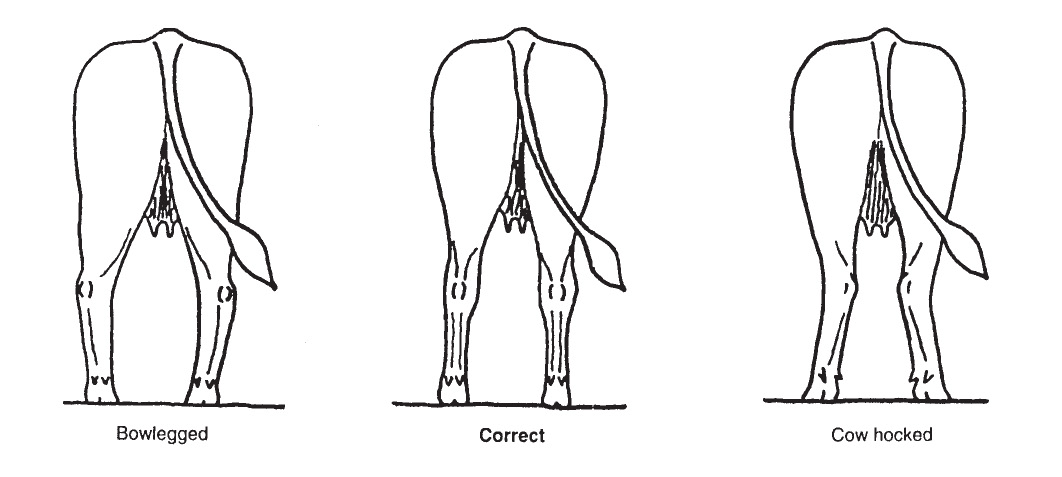

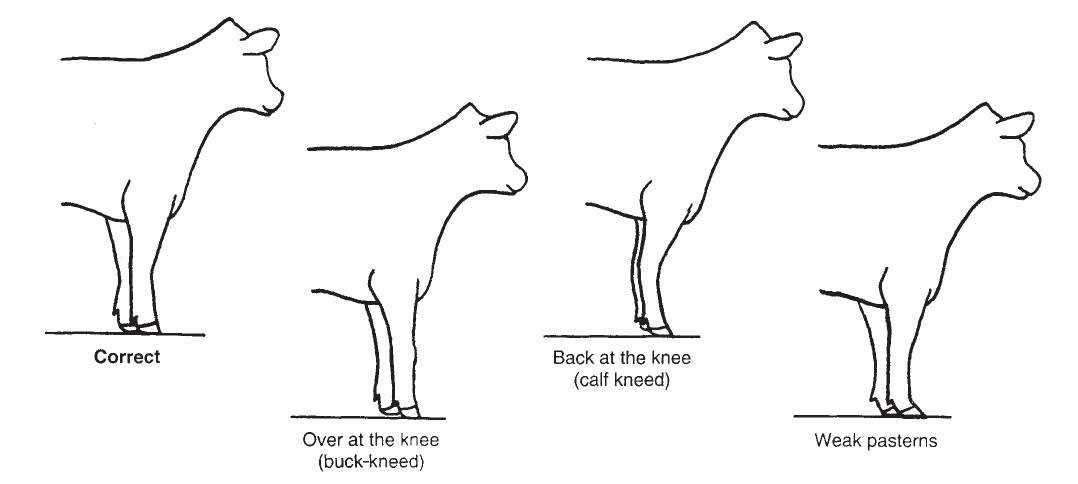

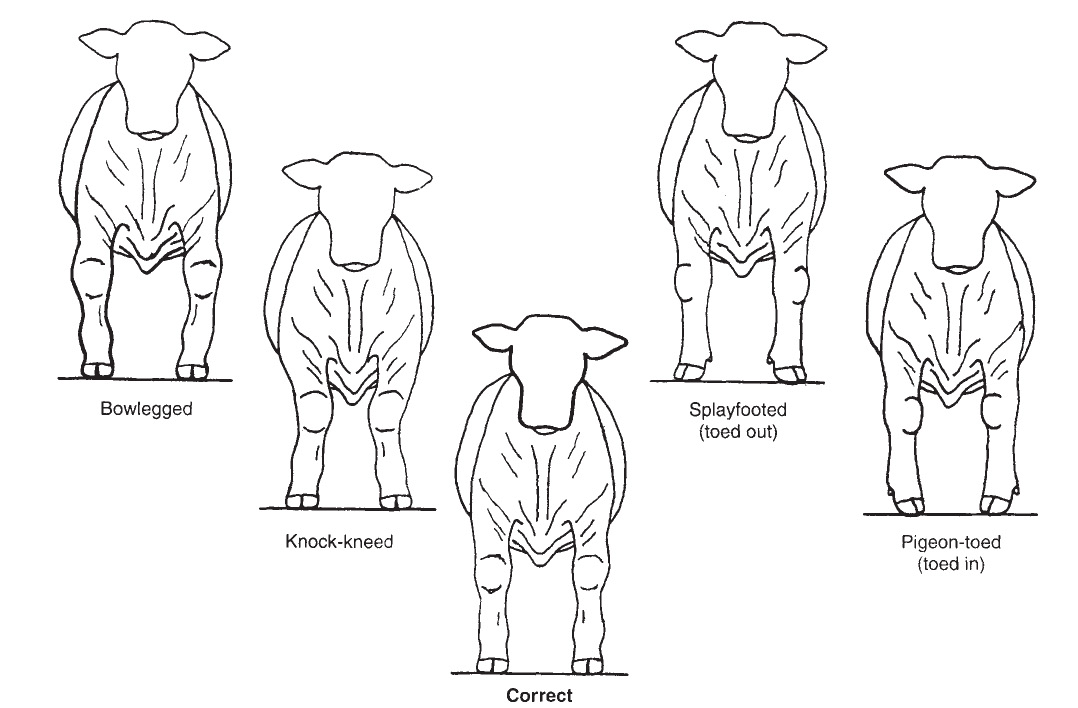

Feet and leg placement is illustrated in Figures 7 through 10.

|

|

Normal range |

Average |

Ideal |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Live weight (lb) |

900-1400 |

1150.0 |

1220.0 |

|

Dressing percentage |

55-67 |

62.0 |

62.0 |

|

Fat thickness (in) |

.15-1.0 |

.50 |

.30 |

|

Ribeye area (sq. in) |

8-16 |

11.5 |

13.3 |

|

KPH fat percentage |

1-6 |

3.5 |

2.0 |

|

Quality grade |

Low Select-Avg.Prime |

Low Choice |

Avg. Choice |

Adapted from Live Animal Carcass Evaluation and Selection Manual, 4th edition, 1993, Donald L. Boggs and Robert A. Merkel.

Handling Market Steers

There are no predetermined guidelines for handling steers. The primary objectives when handling steers are to estimate accurately the amount and uniformity of finish and to determine the quantity of muscle in the loin – and maybe in the rump or in the quarter – as an indicator of total muscle volume.

Cup your hand and place the palm of your hand on the loin of the steer and evaluate the depth and width of his loin. The loin should be wide and deep with muscle.

Beef Cattle Terminology

General

More Desirable Characteristics

- more progressive

- more dimensional

- stouter

- more upstanding

- growthier

Less Desirable Characteristics

- conventional

- needs more size and performance

- lacks growth and do-ability

Structure

More Desirable Characteristics

- fault free

- problem free

- straighter lined

- more structurally correct

- better balanced

- tighter framed

- stronger topped, loined

- squarer, leveler rumped

- higher and wider at the pins

- more nearly level in the rump

Less Desirable Characteristics

- ill structured

- poorer structured

- slack framed

- structurally incorrect, poorer structured

- more off-balance, poorly balanced

- weaker topped, loined

- dropped at the pins

- narrower at the pins

- steeper in the rump

Frame and Growth

More Desirable Characteristics

- more moderate framed

- larger framed

- smaller framed

- more size and scale

- longer ______

- more ruggedly designed

- higher weight per day of age

- more performance oriented

Less Desirable Characteristics

- smaller framed or larger framed

- smaller framed

- larger framed

- lacks size and scale

- shorter _______

- finer boned, frailer made

- lower weight per day of age

- lacks growth and performance

Head, Neck, Chest, and Shoulder

More Desirable Characteristics

- fresher appearing

- later maturing

- more future growth potential

- more extended through the front end

- longer, leaner neck

- laid in more neatly about the shoulder

- smoother, tighter shouldered

- smoother neck/shoulder junction

- more desirable slope to the shoulder

- wider chested

Less Desirable Characteristics

- staler appearing

- earlier maturing

- less future growth potential

- shorter fronted

- shorter, leathery fronted

- coarser fronted

- more open shouldered

- coarser neck/shoulder junction

- straight shouldered

- narrower chested

Condition

More Desirable Characteristics

- trimmer, cleaner patterned

- cleaner conditioned

- more ideal in (his/her) condition

- trimmer dewlap, brisket

- easier fleshing

Less Desirable Characteristics

- heavy conditioned

- less ideal in (his/her) condition

- wastier through the front end

- harder doing, harder fleshing

Volume and Capacity

More Desirable Characteristics

- wider sprung

- deeper ______

- more capacious, higher capacity

- bigger volumed

- more dimensional ______

- more arch and spring of rib

- bolder spring of rib

- longer ribbed

- more dimension through center of the rib

Less Desirable Characteristics

- narrower made

- shallower _______

- less capacious

- less volume

- less dimensional _______

- flatter ribbed

- pinched in the forerib

- shorter ribbed

- less dimension through the center of the rib

Muscle and Muscle Design

More Desirable Characteristics

- longer, smoother muscle design

- ______ muscle make-up

- heavier muscled

- thicker made

- deeper quartered

- thicker top

- thicker loin

Less Desirable Characteristics

- shorter, tighter muscle design

- lighter muscled

- shallower quartered

- narrow topped

Feet and Legs

More Desirable Characteristics

- stood on more bone

- heavier boned

- stood on more rugged bone

- stood squarer in (his/her) foot placement

- greater diameter of bone

- stands wider both front and rear

- more desirable set to the hock

- stronger pasterns

Less Desirable Characteristics

- stood on more bone

- finer boned

- stood on finer bone

- splayfooted, pigeon-toed, toes out

- stands narrower both front and rear

- posty legged, sickle hocked

- weak pasterned

Stride and Movement

More Desirable Characteristics

- more mobile

- more fluid moving

- easier moving, sounder footed

- moved out freer and easier

- farther reaching in (his/her) stride

- truer tracking

- longer strided

- moves with more strength of top

- moves with more levelness of rump

Less Desirable Characteristics

- restricted in (his/her) movement

- stiff strided

- narrower tracking, cow hocked

- shorter strided

- roaches (his/her) top on the move

- drops (his/her) pins on the move

Bull

More Desirable Characteristics

- stouter

- more powerful

- cleaner sheath

- neater sheath

- more scrotal circumference

- greater testicular development

- more testicular distention

- more uniform-sized testicles

- testicles hang more correctly

- more ruggedly designed

- wider chested

Less Desirable Characteristics

- pendulous sheath

- less scrotal circumference

- less testicular development

- less testicular distention

- uneven-sized testicles

- twisted testicles

- narrower chested

More Potential to Sire Calves with _______

- frame

- length

- volume

- growth

- muscle

- trimness

- performance

- weight per day of age

Less Potential to Sire Calves with _______

- frame

- length

- volume

- growth

- muscle

- performance

- weight per day of age

Should Sire Calves with more _______

- frame

- length

- volume

- growth

- muscle

- trimness

- performance

- weight per day of age

Should Sire Calves with less _______

- frame

- length

- volume

- growth

- muscle

- performance

- weight per day of age

Heifer

More Desirable Characteristics

- broodier

- more angular

- more stylish

- easier fleshing

- easier keeping

- combines correctness, length, and eye appeal

- nicer brood cow prospect

- larger vulva

- trim-clean navel

Less Desirable Characteristics

- less angular, coarser

- harder fleshing

- harder keeping

- smaller vulva

- loose, wasty navel

Steer

More Desirable Characteristics

- moderate framed

- nicer balanced

- tighter framed

- trimmer, cleaner patterned

- heavier muscled

- more total muscle mass

- wider, thicker topped

- wider, more expressively muscled

- longer ______

- deeper, wider, thicker quarter

- pushes more stifle on the move

- more ideally finished

- handles with ______

- cleaner in his condition

- possesses less waste through ______

- trimmer ______

- should rail a carcass with a ______

- higher lean-to-fat ratio

- more desirable yield grade

Less Desirable Characteristics

- taller

- more off-balance

- slack framed

- heavy middled, off-balance

- lighter muscled

- less total muscle mass

- narrow down his top

- shorter ______

- narrower based, lighter muscled quarter

- patchy, uneven finish

- wastier, fatter, overfinished

- wastier ______

- should rail a carcass with a ______

- lower lean-to-fat ratio

- less desirable yield grade

Performance Data for Beef Cattle

Performance data, or performance records, allow producers to objectively evaluate economically important traits associated with livestock production. The major production traits of beef cattle include the following:

- Measurement of reproductive performance and mothering ability

- Quantification of growth rate and efficiency of gain

- Objective analysis of carcass merit

Performance evaluations can be reported as performance records, or as genetic evaluations of those records and of an animal’s relatives.

In the past several years, an ever-increasing emphasis has been placed on the understanding and use of performance evaluations. The next sections will discuss the importance and application of performance evaluations to beef cattle judging and the combined use of visual appraisal and performance records (actual or genetic) for live animal selection.

Beef cattle performance data can be listed in several different ways. For example, an Angus bull calf might have a 600-pound weaning weight, or a Polled Hereford heifer might have a 750-pound yearling weight. Both of these examples represent actual records of the individual, but they don’t depict how these animals have performed relative to other animals in the herd. Therefore, a more accurate representation of performance would be to rank animals within the same herd. However, ranking animals within the same herd can be biased if they are born at different times of the year or if they are housed and managed differently. Thus, we often need to rank animals within a contemporary group, which is comprised of animals that are of the same breed, age, and sex and that have been raised in the same management group (same location and access to the same feed).

Generally, use a ratio to rank animals within a contemporary group in the herd. A ratio consists of a number, typically around 100 (average), that compares each animal to the other animals in a particular group. Any number below 100 indicates that the animal’s performance was below the average of the group. A ratio of 110 for weaning weight means the animal was 10 percent above average for weaning weight. Likewise, a ratio of 85 for weaning weight means the animal was 15 percent below average for weaning weight. However, use of ratios does not indicate the exact average for a certain trait. Also, ratios may only be used to compare animals within a contemporary group.

When judging livestock and evaluating performance records, select animals for a particular purpose. Ideally, a comparison is made between progeny, or offspring, of one animal with progeny of another animal for a certain economically important trait.

Producers need to be able to compare animals on the same farm that were raised in different contemporary groups or to compare one animal on a particular farm with another animal on a different farm. However, neither actual records nor ratios allow producers to compare animals accurately from different contemporary groups or herds.

In order to compare animals accurately within a breed and across different herds, an expected progeny difference (EPD) must be used. EPDs are a reliable tool to predict the true genetic value of an animal because they consider the individual performance of the animals as well as data from parents, full siblings, and other relatives in all herds that report the information. The biggest advantage is that EPDs allow producers to make comparisons across contemporary groups and herds. However, you cannot compare EPDs of one breed against the EPDs of another breed (example: EPDs of Brangus cannot be compared to the EPDs of Angus). Therefore, a bull with a yearling weight EPD of +55.0 would be expected to sire offspring that are 55 pounds heavier at 365 days of age than offspring from a bull with a yearling weight EPD of 0 (zero). Likewise, a bull with a weaning weight EPD of +45.0 would be expected to sire progeny that are 30 pounds heavier at weaning than the average of the progeny from a bull with a weaning weight EPD of +15.0.

The student who wishes to excel in beef cattle judging must fully understand the importance and accuracy of using actual records on an individual, ratios from within a herd, and EPDs for the following beef cattle production traits:

- Birth Date – The actual date an animal was born.

- Birth Weight – The weight of a calf taken at birth. Heavy births are associated with calving problems and sometimes death of the calf or cow (actual, ratio, or EPD). Birth weight EPDs are more reliable than actual birth weights when predicting calving problems.

- Weaning Weight – The weight of a calf taken between 160 and 250 days of age and then adjusted to a constant age of 205 days (actual, ratio, or EPD).

- Yearling Weight – The weight of an animal taken between 330 and 440 days of age and adjusted to a constant age of 365 days (actual, ratio, or EPD).

- Hip Height or Frame Score – Height at the hip in inches, or height at the hip in inches for a particular age (actual or ratio).

- Maternal Milk EPD – The difference in pounds of a calf expected at weaning because of differences in the milking and mothering ability of the cow.

- Yearling Scrotal Circumference – The distance measured in centimeters around the testicles in the scrotum of a bull at 365 days of age. A greater scrotal circumference indicates that a bull should have the capacity to produce greater volumes of semen, and his progeny should reach puberty at earlier ages (actual or ratio).

When presenting more than one type of data for a particular trait, such as ratios and EPDs for weaning weight, rank and use the data according to the accuracy with which future performance of offspring can be predicted. Give emphasis to the data in the following sequence:

- EPD

- Ratio within a contemporary group

- An individual animal’s actual records

Production Situations for Beef Cattle

The types of beef cattle data and the selection of livestock based solely on visual appraisal have been discussed previously. When practical, use additional information to aid in the selection process. The availability of actual data, ratios, and EPDs allows judges to compare animals using objective criteria of performance. However, without some guidelines, the justifications for various placings of a class with performance data may be even more numerous than the reasons based on visual appraisal alone.

Understanding the scenario is possibly the most important factor when placing a performance class. A scenario is the assumed situation you are in while ranking the class. In each scenario, address three important factors for a complete description:

Breeding Program

- What type of breeding program is being used?

- How are the selected animals to be used in that program?

- What are the goals or objectives of this breeding program?

Feed and Labor Resources

- Under what conditions are the animals being raised?

- Are feed resources readily available or limited?

- Are labor resources readily available or limited?

Marketing Program

- How are the cattle marketed?

- At what age and/or weight are the cattle to be sold?

- For what type of buyer are the cattle being produced?

Using the three factors discussed above, analyze the following three scenarios and data:

Scenario 1

Angus Bulls

These bulls will be used as natural service sires in a two-breed rotational crossbreeding system with Hereford. Cows are medium mature weight and moderate for milk production, and they will be maintained similar to range conditions, with low labor and limited feed availability for larger sizes of cattle. The top 20 percent of heifer calves will be retained as replacements, and the remaining heifer and steer calves will be sold at weaning to be finished in a feedlot.

|

No. |

Birth date |

Birth weight EPD |

Weaning weight EPD |

Yearling weight EPD |

Maternal milk EPD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 (7028) |

2/06/97 |

+2.1 |

+26.0 |

+35.0 |

+5.0 |

|

2 (7126) |

2/25/97 |

+0.9 |

+33.0 |

+59.0 |

+11.0 |

|

3 (7003) |

1/28/97 |

+5.3 |

+29.0 |

+38.0 |

-3.0 |

|

4 (7114) |

2/24/97 |

+4.0 |

+28.0 |

+40.0 |

0.0 |

|

Breed Avg. EPDs: |

+3.0 |

+29.1 |

+52.5 |

+11.5 |

|

Scenario 2

Simmental Heifers

These heifers will be used in a purebred Simmental herd that produces commercial bulls. The bulls will be used on Angus x Polled Hereford crossbred cows and heifers. Mature cow size in the commercial herd is 1,000 to 1,150 pounds. Feed and labor resources in this purebred Simmental herd are adequate to maintain a mature cow size of 1,300 to 1,500 pounds. The primary income is from the sale of commercial bulls, but some income is from the sale of a few purebred bulls and heifers to other purebred Simmental breeders.

|

No. |

Birth date |

Birth weight EPD |

205-day weight EPD |

365-day weight EPD |

Maternal milk EPD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

1/30/94 |

+4.7 |

+24.2 |

+44.0 |

+1.5 |

|

2 |

3/01/94 |

+11.1 |

+42.7 |

+68.0 |

+11.0 |

|

3 |

1/22/94 |

+4.0 |

+28.0 |

+51.0 |

+1.0 |

|

4 |

2/11/94 |

+3.8 |

+24.0 |

+53.0 |

+0.8 |

|

Breed Avg. EPDs: |

+3.3 |

+21.0 |

+33.8 |

+0.6 |

|

Scenario 3

Brangus Bulls

Rank these bulls in the order they should be selected as potential herd bulls for a commercial cattle operation. This progressive ranch is looking for a terminal sire to breed to 1,200-pound Black Baldie cows (Angus X Hereford). The progeny from these bulls will be retained by the ranch in the feedlot and sold on a value-based program using a grid that pays premiums for high cutability cattle. Feed and labor resources are abundant.

|

No. |

Tag |

Birth weight EPD |

Weaning weight EPD |

Yearling weight EPD |

Maternal milk EPD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

604 |

+3.9 |

+18.2 |

+33.0 |

+4.0 |

|

2 |

666 |

+1.3 |

+9.8 |

+25.0 |

+5.4 |

|

3 |

699 |

-1.5 |

+19.2 |

+43.0 |

-1.0 |

|

4 |

714 |

+3.2 |

+28.5 |

+47.9 |

+1.8 |

|

Breed Avg. EPDs: |

+1.3 |

+15.5 |

+27.1 |

+0.9 |

|

First, describe the breeding program. Is this a purebred or a commercial operation? If cattle are crossbred in this operation, what other breeds are being used? A class of heifers could be replacement females for a purebred program, or a class of bulls could be intended as natural service sires for a purebred or a commercial program. Regardless of the situation, outline an accurate and complete description of the breeding program. Following are analyses of scenario examples of possible breeding programs:

Angus Bulls – Use them as natural service sires in a two-breed rotational crossbreeding system with Hereford. Cows are medium for mature weight and moderate for milk production.

Simmental Heifers – Assume these heifers will be used in a purebred Simmental herd that produces commercial bulls. The bulls will be used on Angus x Polled Hereford crossbred cows and heifers. Mature cow size in the commercial herd is 1,000 to 1,150 pounds.

Brangus Bulls – Use them as natural terminal service sires in a commercial operation with 1,200-pound Black Baldie cows (Angus X Hereford).

Second, discuss the feed and labor resources. Specifically, describe the quality and quantity of feed. For example, cattle that are managed on low-feed resources or range conditions need ample capacity to efficiently use the limited nutrients and probably should not have excessively high milk production. Labor resources will impact body type and birth weight performance records of cattle to be selected. Cattle with high birth weight, coarse shoulders, and narrow rump design with narrow pin placement typically require more physical-labor assistance in the calving process than cattle with low birth weight, smooth shoulders, and wide rump design with added width at the pins. Even with adequate labor available at calving, calves with high birth weights can create unwanted problems and economic hardships for cattle producers. Feed and labor resources are as follows:

Angus Bulls – Cows bred to these bulls will be maintained similar to range conditions, with low labor and limited feed availability for larger sizes of cattle.

Simmental Heifers – Feed and labor resources in this purebred Simmental herd are adequate to maintain a mature cow size of 1,300 to 1,500 pounds.

Brangus Bulls – Feed and labor resources are abundant.

Third, the scenario should discuss the marketing program in enough detail so that performance traits and physical characteristics of the animals can be prioritized. Depending on the marketing program used, place emphasis on traits and characteristics that optimize production of beef cattle for the desired market. Examples follow of marketing programs from each scenario:

Angus Bulls – Retain the top 20 percent of heifer calves as replacements and sell the remaining heifer and steer calves at weaning to be finished in a feedlot.

Simmental Heifers – Sale of commercial bulls is the main benefit, but some income comes from the sale of a few purebred bulls and heifers to other purebred Simmental breeders.

Brangus Bulls – The ranch retains the progeny in the feedlot and sells on a value-based program using a grid that pays premiums for high cutability cattle.

After looking at each part of the scenarios, consider the following priorities:

Scenario 1

Priorities: Select bulls that will maintain mature weight and milk production (maternal traits – birth weight EPD and maternal milk EPD). Maternal traits are very important because top heifers are retained. Remaining heifers and steers are sold at weaning; therefore, paternal traits (weaning weight EPD) are very important.

Scenario 2

Priorities: Maintain a balanced program in all areas. Select cattle that maintain or slightly increase performance in maternal (birth weight EPD and maternal milk EPD) and paternal (weaning weight EPD and yearling weight EPD) traits. Extremes are faulted.

Scenario 3

Priorities: Select bulls that will produce fast-growing calves; therefore, paternal traits (yearling weight EPD) are very important. Material traits in this scenario are not really considered because of the abundance of labor and feed; however, extremes are faulted.

Sample Oral Reasons for Beef Cattle

Prepared by Jeremy White, former Union County 4-H’er

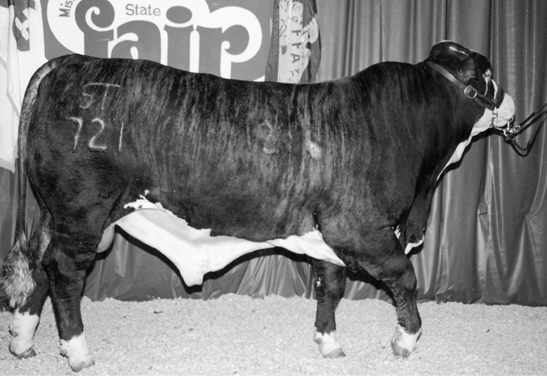

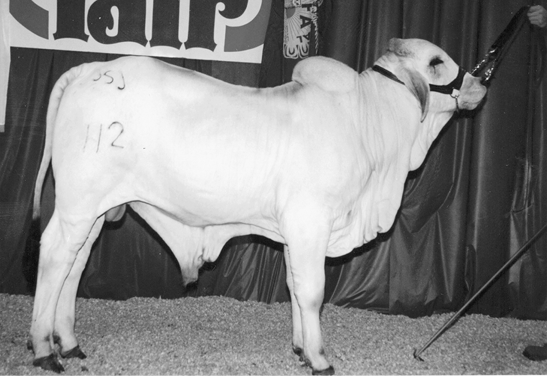

Junior Yearling Brangus Heifers

3-4-2-1

“After analyzing this class of Brangus heifers, my placings were 3-4-2-1. I started with the split-eared heifer in the class, as she was the freest-moving and the longest, smoothest muscled, patterned heifer in the class. I realize 3 could have been heavier muscled throughout; nonetheless, I used 3 over 4 in my top pair, as 3 was a more moderate framed, smoother shouldered heifer that shows more femininity and refinement about her front. She was especially freer from excess leather in the dewlap and brisket and was cleaner and trimmer in the navel. 3 was the most progressive heifer in terms of her muscle length and smoothness, and she moved out with a freer, easier, and more ground-covering stride. She stood on more length of cannon and more closely follows that modern Brangus ideal. I must admit that 4 was a deeper ribbed heifer that showed more thickness down her top and through the center and lower portions of her quarter, while standing on more substance and diameter of bone. However, I would like to see 4 flatter and smoother in her muscle structure and more refined about her front end.

In spite of this, I preferred 4 over 2 in my middle pair, as 4 more closely followed my top heifer in terms of skeletal size and scale. Of the pair, 4 was a larger framed, deeper ribbed, wider sprung, higher capacity heifer that exhibited more total volume and capacity from end to end. She was a more ruggedly made heifer that showed more thickness of muscling down her top and through all dimensions of her quarter. She stood on more substance of bone and more correctly on her feet and legs. I must admit that 2 did more closely follow my top heifer in terms of muscle length and smoothness and was more refined about her front end, but she splayed out up front and was cow hocked.

But I did prefer to use 2 over 1 in my bottom pair of smaller framed heifers, as 2 was a growthier heifer that was cleaner about her middle, trimmer about her front, and showed more youthfulness and growth potential about her head and neck. She was more progressive in her muscle length and smoothness and blended in neater and smoother through her shoulders. She appeared to be a later maturing heifer that should grow into a more progressive and productive herd matron. I must admit that 1 was a straighter, stronger topped, leveler rumped heifer that was more structurally correct, but I faulted 1 and placed her last in this class as she was the smallest framed, lowest set, heaviest fronted heifer that had the most leather in her dewlap, brisket, and navel. She lacked the overall size, scale, balance, and smoothness of the heifers placed above her in the class today. Thank you.”

2-1-4-3

“Selecting the most production-oriented heifer that best combines volume, structural soundness, and balance, I chose the alignment 2-1-4-3 for the Limousin heifers. I realized 2 could be trimmer in her condition and wider tracking, but compared to 1 in my initial pair, she was a broody-appearing, easy-fleshing heifer that carried more length and spring from fore to rear ribs.

Sure, 1 was a stout-made, powerfully constructed heifer, but she was short bodied and restricted in her movement. However, with these faults aside, it was the muscle and volume of 1 over the balance of 4. Also, 1 was wider chested, being deeper and bolder sprung. Likewise, she carried more width and dimension down her top while maintaining this advantage into a more three-dimensional quarter.

Yes, 4 was a more feminine-fronted heifer, but at the same time, she was narrow tracking off both ends and tapered through her lower quarter. Even so, in my concluding pair, 4 beat 3. She was a more attractive profiling, more eye-appealing heifer that was more angular fronted. In addition, she was straighter, stronger down her top, and longer and leveler out of her hip, allowing her to be longer striding off her rear legs.

I realize 3 was a long-bodied, deep-sided heifer. However, this does not allow for the fact that she was the narrowest made, lightest muscled heifer that was the poorest structured; so she was last. Thank you.”

4-2-1-3

“My placing of the market steers is 4-2-1-3. I started the class with 4, the most powerfully muscled, most correctly finished steer in the class. I realize he was wastier fronted and middled; nonetheless, I used 4 over 2 in my top pair because he was a thicker made, heavier muscled steer throughout. He was a leveler topped steer that was longer in his rump. He had more thickness working down his top and out through a fuller rump. As viewed from behind, he had more thickness of muscle in the upper and center portions of his quarter and pushed more stifle on the move. He handled with more condition over his loin edge and down over his rib and should be more apt to reach that Choice quality grade. However, I do realize that 2 was a cleaner middled, trimmer fronted steer, but he simply lacked the volume and dimension of muscle of my top steer.

Concerning my middle pair, I placed 2 over 1, as 2 was a longer bodied, more upstanding steer that was trimmer through his front and middle. As viewed from behind, he had more thickness through the center and lower portions of his quarter and should go to the rail and hang a higher cutability carcass. I will admit that 1 was a deeper ribbed, wider sprung, higher capacity steer that stood down on more substance of bone. Also, he was a squarer rumped steer that was more ideal in the amount and uniformity of his finish.

I confidently placed 1 over 3 in my bottom pair, as he was a thicker made, heavier muscled steer that was more nearly ideal in his finish. He had more natural thickness down his top and through his quarter. He should hang a heavier muscled carcass that should be more likely to grade Choice. I do realize that 3 was a trimmer made steer, having less waste throughout. However, he was the lightest muscled, most underfinished steer of the class. He would hang up the least merchandizable carcass and, therefore, cannot merit a higher placing today. Thank you.”

1-4-2-3

“With the given scenario in mind, I placed my emphasis on weaning and yearling weight expected progeny differences as well as structural correctness and found that 1 best satisfied the scenario.

I realize 1 was not the highest in his growth data. Even so, the dehorned bull easily beats 4 in the top pair as he was the heaviest muscled, nicest balanced, easiest fleshing bull in the class. Plus, he’s the deepest ribbed, the heaviest boned, and the straightest in his lines.

Yes, 4 had the highest weaning and yearling weight EPDs, but he was also the poorest structured bull that was straight in his shoulder and hock, was steep hipped, and was restricted in his movement, so he’s second.

Still, I opted to use 4 over 2 in the middle pair, as 4 simply dominated in terms of weaning and yearling weight EPDs. In addition, he’s a larger framed bull that was stronger topped, smoother shouldered, and cleaner fronted.

I admit 2 was leveler hipped and took a longer, freer stride from behind, but his weaning weight EPD of +6.9 was the lowest in the class; he’s deep and course fronted, weak topped, and sickle hocked, so he’s third.

Even so, I used 2 over 3 in the bottom pair as he’s higher in his yearling weight EPD. He was thicker down his top and through his quarter, leveler hipped, and he tracked wider based behind.

I realize 3 was taller fronted, deeper ribbed, and straighter on his hind legs. But, at 9.7, he had the lowest yearling weight EPD of the class. He was the lightest muscled, narrowest chested, hardest doing bull that’s steep hipped and twisted in his scrotum, so he’s last. Thank you.”

Sheep

Breeds of Sheep

Table 5 outlines some of the breeds of sheep that are common in the United States. Each breed has been assigned a breed class (ram, ewe, or dual) according to whether the dominant characteristics of the breed are associated with growth and carcass traits (ram) or reproductive characteristics (ewe). The dual breed class indicates that the breed is noted equally for growth, carcass, and reproductive characteristics.

Average weights for mature rams and ewes are listed. Again, these are included to allow you to compare one breed with another breed. The weights and other characteristics listed are breed averages; there is as much variation within a breed as there is among breeds for these traits.

Growth rate, hardiness, gregariousness, prolificacy, and milking ability are ranked among breeds, using a 6-point scale, with 1 as the most desirable and 6 as the least desirable. Fleece weight is given in pounds of wool per year from the average animal of that breed. Fleece type is listed as either fine, medium, or long and describes the type of wool fiber characteristic of the breed.

|

Breed |

Breed class |

Ram wt. |

Ewe wt. |

Growth ratea |

Hardinessa |

Gregariousnessa |

Prolificacya |

Milking abilitya |

Fleece weight |

Wool type |

Face color |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Border Leicester |

ram |

210 |

160 |

4 |

6 |

6 |

3 |

3 |

9 |

long |

white |

|

Cheviot |

ewe |

180 |

135 |

4 |

4 |

6 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

medium |

white |

|

Columbia |

dual |

260 |

165 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

11 |

medium |

white |

|

Corriedale |

ewe |

190 |

140 |

5 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

11 |

medium |

white |

|

Debouillet |

ewe |

190 |

140 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

5 |

5 |

11 |

fine |

white |

|

Delaine |

ewe |

195 |

130 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

5 |

5 |

11 |

fine |

white |

|

Dorset |

dual |

225 |

170 |

3 |

6 |

6 |

3 |

2 |

6 |

medium |

white |

|

Finnsheep |

ewe |

200 |

140 |

5 |

6 |

6 |

1 |

2 |

6 |

medium |

white |

|

Hampshire |

ram |

275 |

200 |

2 |

6 |

6 |

3 |

2 |

7 |

medium |

black |

|

Lincoln |

dual |

300 |

225 |

5 |

6 |

6 |

4 |

5 |

12 |

long |

white |

|

Montdale |

ram |

235 |

160 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

4 |

4 |

8 |

medium |

white |

|

Oxford |

ram |

250 |

190 |

3 |

6 |

6 |

4 |

4 |

8 |

medium |

brown |

|

Rambouillet |

ewe |

225 |

160 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

5 |

5 |

11 |

fine |

white |

|

Romney |

dual |

220 |

175 |

5 |

6 |

6 |

4 |

5 |

10 |

long |

white |

|

Shropshire |

ram |

235 |

170 |

3 |

5 |

6 |

3 |

3 |

8 |

medium |

dark brown |

|

Southdown |

ram |

200 |

145 |

4 |

6 |

6 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

medium |

light brown |

|

Suffolk |

ram |

300 |

215 |

1 |

6 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

5 |

medium |

black |

|

Targhee |

ewe |

250 |

175 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

11 |

medium |

white |

aRanking based on 1 (most desirable) through 6 (least desirable).

(Adapted from The Sheepman’s Production Handbook, 1982, George E. Scott, editor)

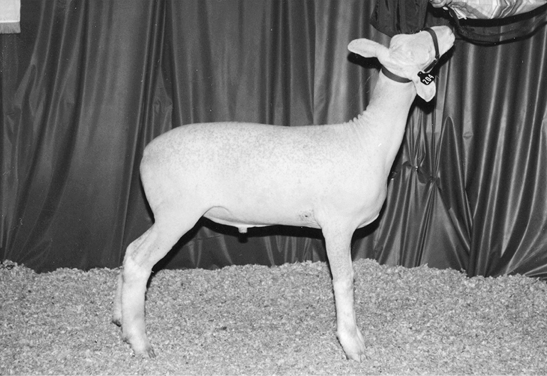

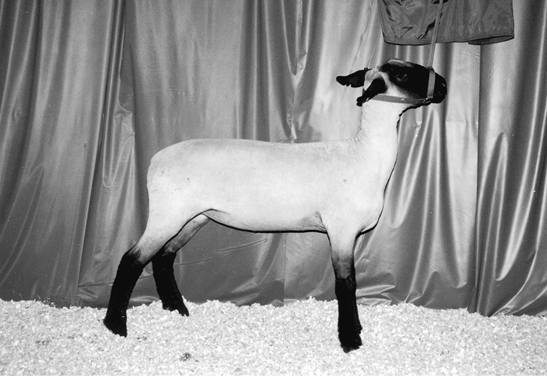

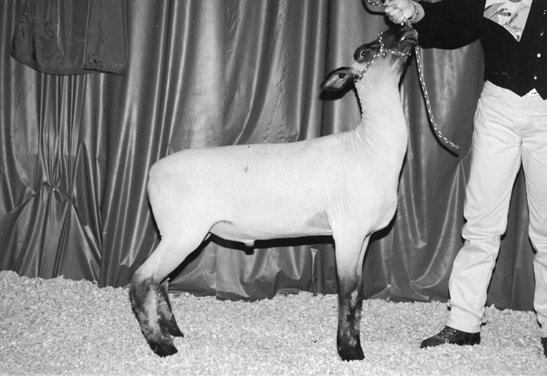

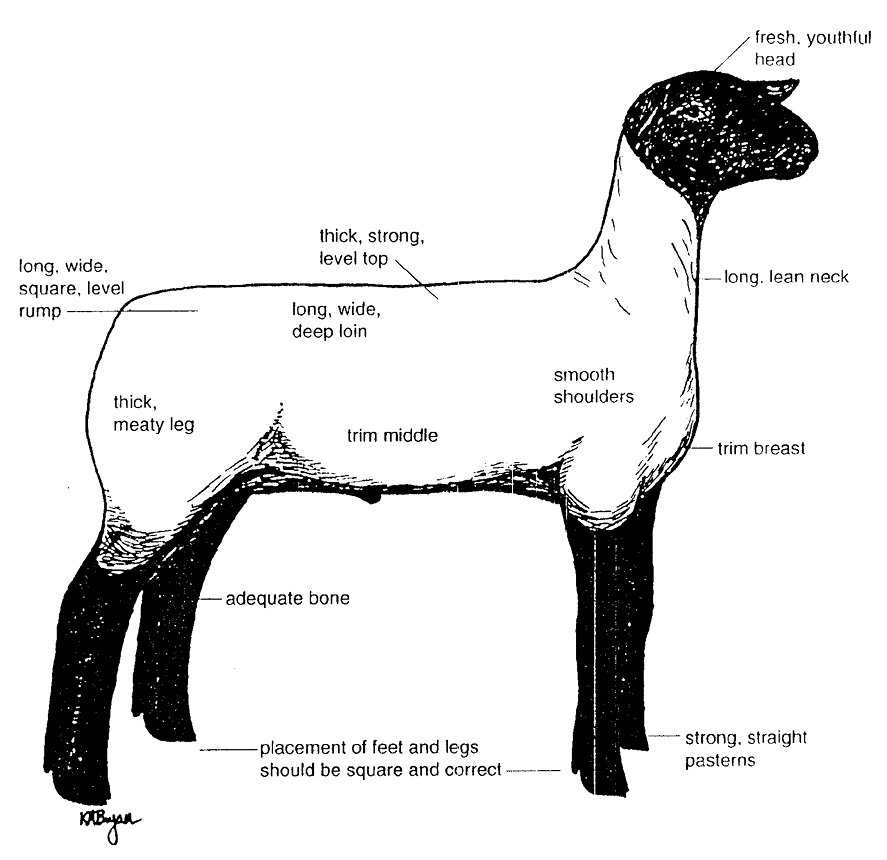

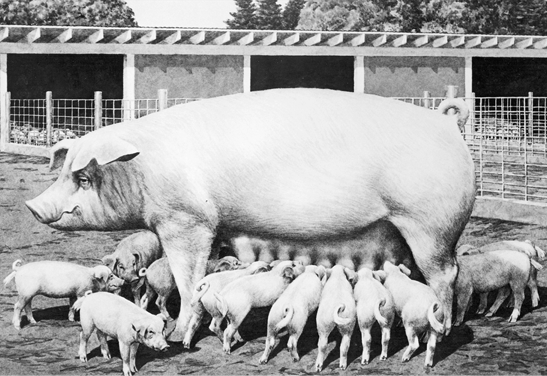

Parts of Sheep

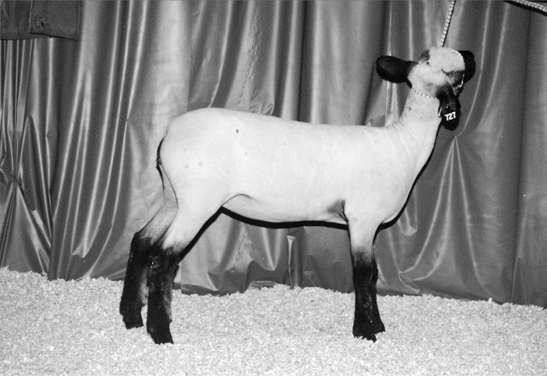

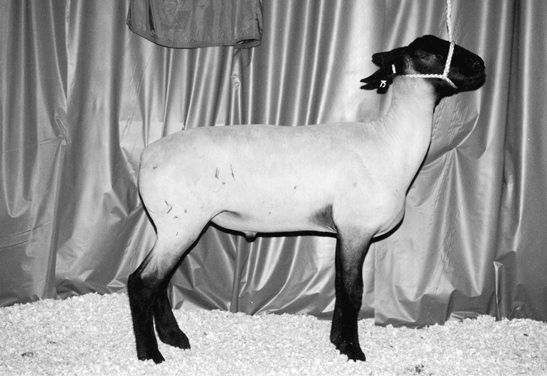

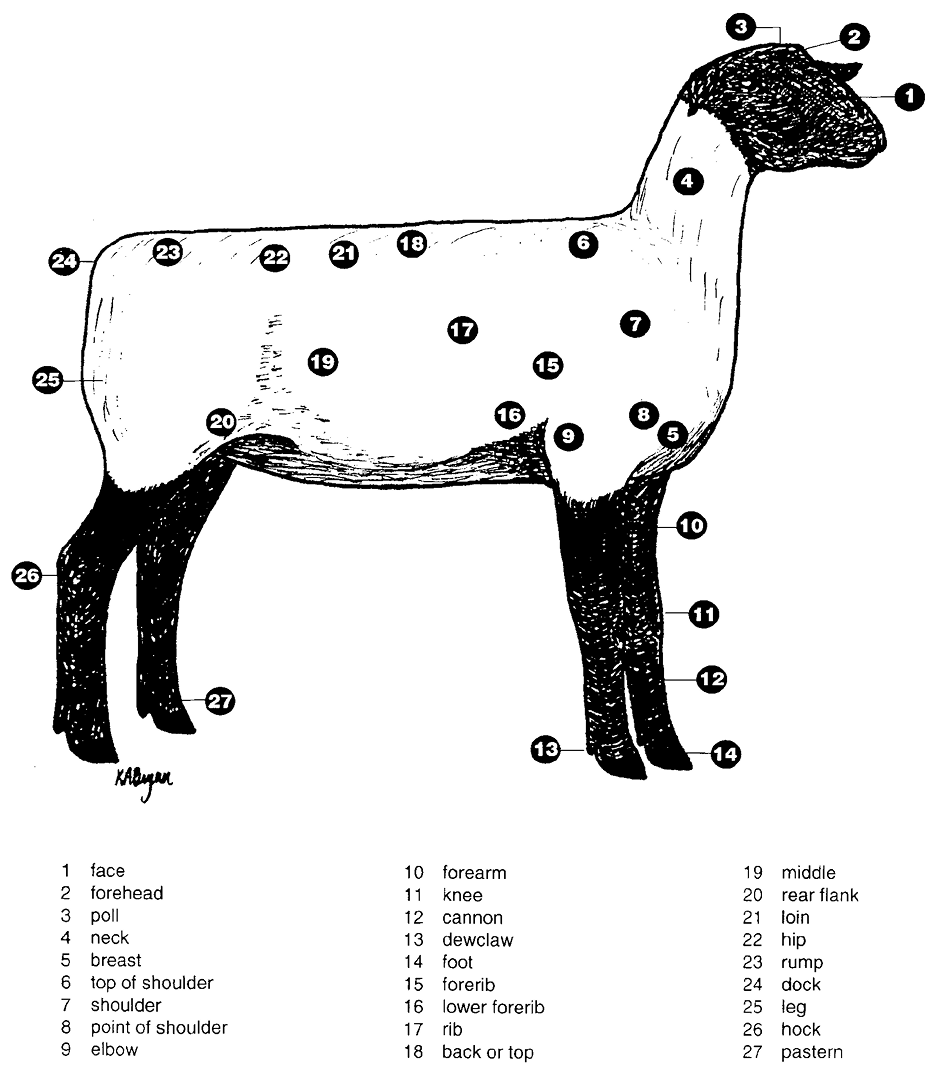

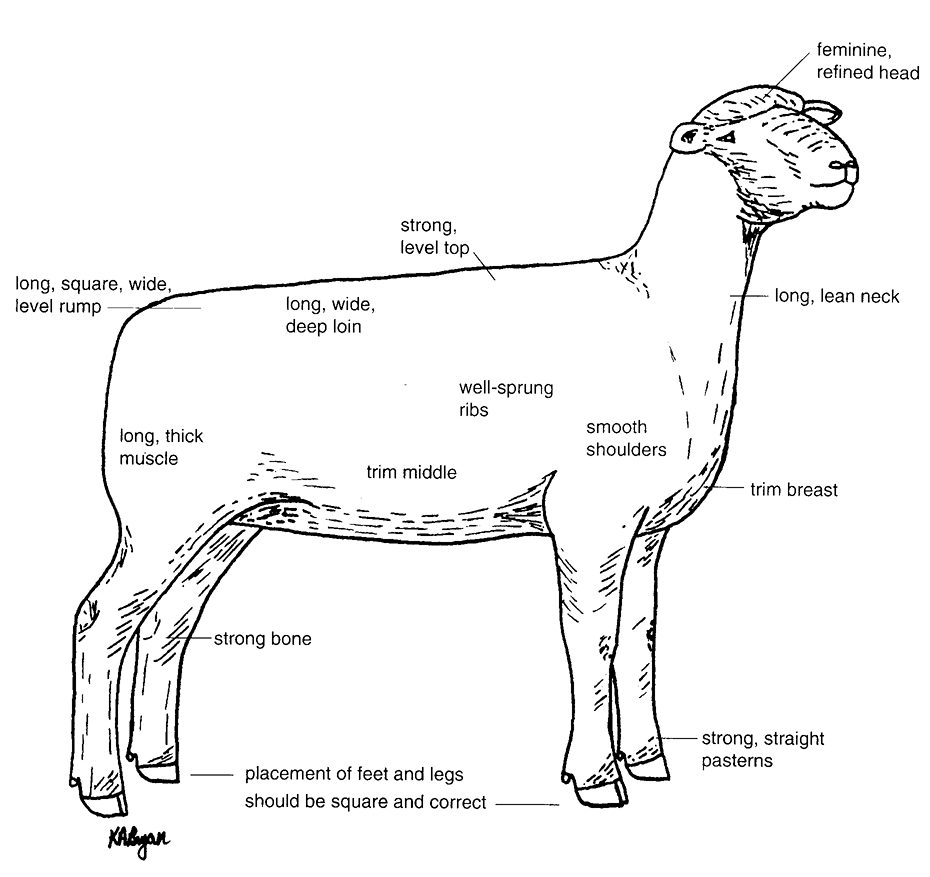

Become familiar with the parts and carcass regions of sheep. In this section, you are provided diagrams of the external parts of sheep (Figure 11), characteristics of an ideal breeding ewe (Figure 12), and characteristics of an ideal market wether (Figure 13). After becoming familiar with all the parts, use those terms as part of your reasons.

|

|

Normal Range |

Average |

Ideal |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Live weight (lb) |

|

110.0 |

120.0 |

|

Dressing percent |

|

52.0 |

52.0 |

|

Fat thickness (in) |

|

.30 |

.12 |

|

Ribeye area (sq. in) |

|

2.25 |

2.80 |

|

KP fat percent |

|

3.5 |

2.0 |

|

Leg Score |

|

|

|

Adapted from Live Animal Carcass Evaluation and Selection Manual, 4th edition, 1993, Donald L. Boggs and Robert A. Merkel.

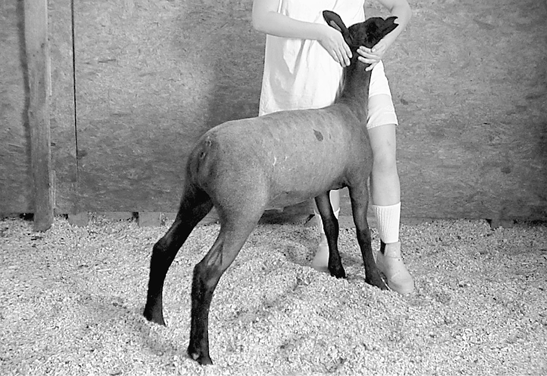

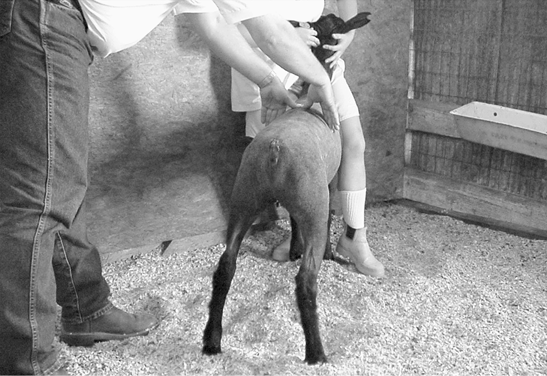

Handling Market Lambs

One key to handling market lambs is to develop a system to accurately determine differences in muscle and finish. Handle each lamb in the same manner. If you handle one lamb from rear to front for finish or fleshing on the back, handle all the lambs that way. Following are the steps for handling market lambs:

Step 7. The final location used to determine the finish of a lamb is at the last rib. Lambs should feel trimmer at the last rib compared with the forerib. Trim, muscular lambs are firm and hard when handled. Fat lambs are soft to the touch, and it is difficult to distinguish the bones of the shoulder, spine, and ribs.

Sheep Terminology

General

More Desirable Characteristics

- more progressive

- more dimensional

- stouter

- more upstanding

- growthier

Less Desirable Characteristics

- conventional

- needed more size and performance

- low fronted

- lacked growth and do-ability

Structure

More Desirable Characteristics

- more fault free

- more problem free

- straighter lined

- more structurally correct

- nicer balanced

- tighter framed

- stronger topped, loined

- squarer, leveler rumped

- more nearly level in (his/her) rump

Less Desirable Characteristics

- ill structured

- poorer structured

- slack framed

- structurally incorrect, poorer structured

- off balance

- weak topped, weaker loined

- dropped at the dock

- steeper in (his/her) rump

Frame and Growth

More Desirable Characteristics

- larger framed

- more size and scale

- longer _______

- more ruggedly designed

- higher weight per day of age

- more performance oriented

Less Desirable Characteristics

- smaller framed

- lacked size and scale

- shorter _______

- finer boned

- lower weight per day of age

- lacked growth and performance

Head, Neck, and Shoulder

More Desirable Characteristics

- fresher appearing

- later maturing

- more future growth potential

- more extended through the front end

- longer, leaner neck

- laid in more neatly about the shoulder

- smoother, tighter shouldered

- smoother neck/shoulder junction

- more desirable slope to (his/her) shoulder

Less Desirable Characteristics

- staler appearing

- earlier maturing

- less future growth potential

- shorter fronted

- shorter, more pelty in (his/her) neck

- coarser fronted

- more open shouldered

- coarser neck/shoulder junction

- straighter shouldered

Condition

More Desirable Characteristics

- trimmer, cleaner patterned

- cleaner conditioned

- more ideal in (his/her) condition

- trimmer breasted

- easier fleshing

Less Desirable Characteristics

- heavier condition

- wastier through (his/her) breast

- harder fleshing, harder doing

-

Volume and Capacity

-

More Desirable Characteristics

- wider sprung

- deeper _______

- higher capacity

- more capacious

- more internal volume

- more dimensional _________

- more arch and spring of rib

- bolder spring of rib

- more dimension through the center of the rib

Less Desirable Characteristics

- narrower made

- shallower _________

- shallower bodied, tighter ribbed

- less capacious

- less internal volume

- less dimensional _______

- flatter ribbed

- pinched or constricted in the forerib

- less dimension through the center of the rib

Muscle

More Desirable Characteristics

- longer, smoother muscle design

- _______ muscle make-up

- heavier muscled

- thicker made

- more expressively muscled in (his/her) leg

Less Desirable Characteristics

- shorter, tighter muscle design

- lighter muscled

- lighter muscled in (his/her) leg

Feet and Legs

More Desirable Characteristics

- stood on more bone

- heavier boned

- stood on more rugged bone

- stood squarer in (his/her) foot placement

- stood wider both front and rear

- more desirable set to the hock

- stronger pasterns

Less Desirable Characteristics

- stood on finer bone

- finer boned

- splayfooted, pigeon-toed, toes out

- stood narrower both front and rear

- posty legged, sickle hocked

- weaker pasterns

Stride and Movement

More Desirable Characteristics

- more mobile

- more fluid moving

- easier moving, sounder footed

- moved out freer and easier

- farther reaching in (his/her) stride

- truer tracking

- longer strided

- moved with more strength of top

- moved with more levelness of rump

Less Desirable Characteristics

- restricted in (his/her) movement

- stiffer strided

- shorter strided

- narrower tracking, cow hocked

- roached with (his/her) top on the move

- dropped (his/her) dock on the move

Fleece

More Desirable Characteristics

- freer from black fiber

- tighter, denser fleece

- fleece with finer crimp

Less Desirable Characteristics

- possessed black fiber _______

- pencil fleece, more open fleece

- cottony fleece

Ram

More Desirable Characteristics

- greater scrotal circumference

- “buck”

Less Desirable Characteristics

- smaller scrotal circumference

More Potential to Sire Lambs with _______

- frame

- length

- volume

- balance

- growth

- muscle

- trimness

- performance

- weight per day of age

Less Potential to Sire Lambs with_______

- frame

- length

- growth

- muscle

- performance

- weight per day of age

Should Sire Lambs with more _______

- frame

- length

- volume

- growth

- muscle

- trimness

- performance

- weight per day of age

Should Sire Lambs with less _______

- frame

- length

- balance

- growth

- muscle

- performance

- weight per day of age

Ewe

More Desirable Characteristics

- broodier

- brood ewe prospect

- more feminine

- more stylish

- more capacious

Less Desirable Characteristics

- coarser fronted

- less capacious

Wether

More Desirable Characteristics

- muscle and trimness

- trimmer, cleaner patterned

- trimmer fronted

- cleaner, harder handling

- firmer handling

- handled with ______

- heavier muscled

- more dimensional leg

- wider, fuller rump

- heavier muscled hindsaddle

- should hang a carcass with _____

- should rail a _____ carcass

- trimmer, higher cutability carcass

- carcass with more leg muscle

Less Desirable Characteristics

- wastier fronted, pelty

- overfinished, fatter, wastier

- softer handling

- lighter muscled

- narrower, lighter muscled leg

- narrower rump, pinched at (his/her) dock

- lighter muscled hindsaddle

Performance Data for Sheep

Much like performance data for beef cattle, performance data for sheep can be listed in several different ways. Both actual data and ratios are used to select animals that are superior for lamb and wool production. Performance data are important for selecting replacement animals and culling poor-producing animals. In judging classes, stud rams or ewes in production are typically not evaluated. Therefore, the use of performance data for selecting replacement ewes and potential stud rams is of primary concern.

Familiarize yourself with the following sheep production traits and the associated terms in order to understand performance data for sheep:

- Birth Date – Actual date an animal was born.

- Birth Weight – The weight of a lamb taken within 24 hours after birth. Heavy birth weights are associated with lambing problems (actual, ratio).