Energy in Beef Cattle Diets

Energy Defined

Protein, carbohydrates, and fats provide energy in beef cattle diets. Energy is often referred to as digestible energy, net energy for maintenance (NEm), net energy for gain (NEg), net energy for lactation (NEl), and total digestible nutrients (TDN). On forage and feed quality analysis test results, digestible energy in Mississippi beef cattle diets is most commonly expressed as TDN. For practical purposes of ration balancing and determining energy supplementation needs on forage-based diets, TDN is a key value to consider.

When digestible energy becomes limiting in beef cattle diets, intake and animal performance can suffer. Signs of energy deficiency include lowered appetite, weight loss, poor growth, depressed reproductive performance, and reduced milk production. Providing adequate digestible energy in beef cattle diets is important for animal health and productivity as well as ranch profitability.

Carbohydrates are the main source of energy in beef cattle diets. Carbohydrates are either nonstructural (readily digested by all livestock) or structural (some are digested through fermentation that occurs in the rumen). Ruminant animals, including beef cattle, have the unique ability to digest some structural carbohydrates in plant cell walls as a source of energy through microbial activity in the rumen. Structural carbohydrates include cellulose, hemicelluloses, and lignin. Beef cattle can digest cellulose and hemicelluloses through rumen microbial action but cannot digest lignin.

As plants mature, cell walls become more lignified and less digestible. Forage digestibility declines tremendously when forages become overmature before cutting or grazing. High ambient temperatures tend to increase plant lignification (production of the indigestible compound lignin), thus lowering digestibility in forages.

It is important to provide cattle with adequate amounts of digestible energy for optimal animal performance. Highly lignified forages are slower to digest than less lignified forages and feeds. Increasing lignin levels in forages increases the time the forage spends in the rumen, decreases dry matter intake, and reduces animal performance. While many factors affect forage digestibility and ultimately TDN, the primary factor producers can control is forage maturity.

Energy and Nutrient Requirements

Beef cattle diets in Mississippi are primarily forage-based. Many factors affect digestible energy levels in forage, including forage maturity and species. Cool-season grasses, such as tall fescue and annual ryegrass, generally are more digestible than warm-season grasses, such as bermudagrass and dallisgrass. Cool-season annuals (annual ryegrass, wheat, rye) typically are more digestible than cool-season perennials (tall fescue, orchardgrass). Legumes like clovers and alfalfa generally are higher in digestibility than grasses (Table 1).

|

Forage |

Stage of Maturity |

Total Digestible Nutrients, % of dry matter[1] |

|---|---|---|

|

Alfalfa |

Bud |

64–67 |

|

Alfalfa |

Early flower |

61–64 |

|

Alfalfa |

Mid bloom |

58–61 |

|

Alfalfa |

Full bloom |

50–57 |

|

Corn silage |

Well-eared |

66–71 |

|

Corn silage |

Fair- to poor-eared |

59–66 |

|

Tall fescue, orchardgrass |

Vegetative – boot |

61–66 |

|

Tall fescue, orchardgrass |

Boot – heat |

56–61 |

|

Annual ryegrass |

Vegetative – boot |

63–68 |

|

Annual ryegrass |

Boot – heat |

59–63 |

|

Bermudagrass |

4 week old |

52–58 |

|

Bermudagrass |

8 week old |

45–50 |

|

Pearl millet, sorghum-sudangrass |

– |

50–58 |

|

Red clover |

Early flower |

64–67 |

|

Red clover |

Late flower |

59–64 |

|

Annual lespedeza |

– |

58–62 |

[1]Grass hay, legume hay, and silage containing at least 58 percent, 64 percent, and 65 percent total digestible nutrients, respectively, are considered excellent quality. Grass hay, legume hay, and silage containing below 52 percent, 57 percent, and 55 percent total digestible nutrients, respectively, are considered poor quality. Adapted from Ball et al. (2007).

Energy is more likely than protein to be deficient in forage-based beef cattle diets in Mississippi. Recent 5-year forage test data from the Mississippi State Chemical Laboratory and the Louisiana State University AgCenter Forage Quality Laboratory support this claim.

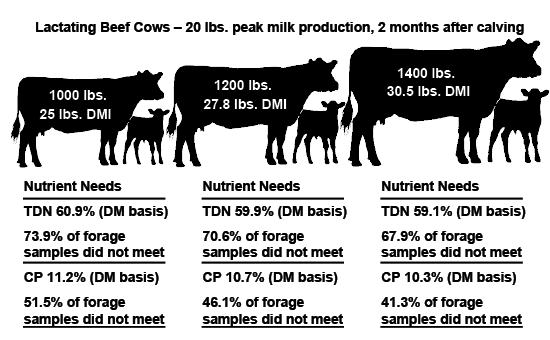

Consider the nutrient demands of a typical 1,200-pound beef cow. Assuming peak milk production of 20 pounds per day, this average cow should consume just under 28 pounds of dry matter each day (DMI = dry matter intake = 28) in the first 2 months after calving. The animal’s nutrient requirements will be approximately 60 percent TDN and 11 percent crude protein on a dry matter (DM) basis. While 46.1 percent of Mississippi forage samples tested would not have met the crude protein requirements of the cow in this example, 70.6 percent of forage samples would not have met the TDN requirements (Figure 1).

Five months after calving, this cow will need 55 percent TDN and 8.5 percent crude protein on a DM basis to support lactation. Only 19.7 percent of forage samples would not have met this crude protein requirement, but 45.7 percent would not have satisfied the TDN requirement. In many other production scenarios, energy content of forages will need supplementation to meet animal nutrient requirements. Monitoring TDN levels in hay and providing acceptable energy in the entire diet is critical for good cattle performance.

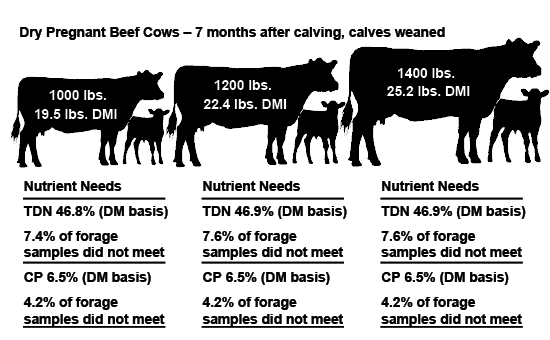

The same cow will have much lower nutrient requirements once her calf is weaned. A dry (non-lactating) beef cow 7 months after calving will need to consume just over 22 pounds of daily DM (DMI = 22) with approximately to 47 percent TDN and 6.5 percent crude protein on a DM basis. The 5-year forage test results indicate that most of the forage samples analyzed would meet these lower dry-cow requirements (92.4 percent of samples would have both adequate TDN and crude protein) (Figure 2). In this case, feeding lower-quality hay to dry cows and saving the better-quality hay for cattle with higher nutrient requirements would be appropriate.

Palatability (the acceptableness of a feed or forage to the animal) and intake can become an issue with lower-quality forages. Make sure cattle receiving lower quality forages have acceptable levels of intake. Monitor cow body condition scores, and adjust energy supplementation as appropriate.

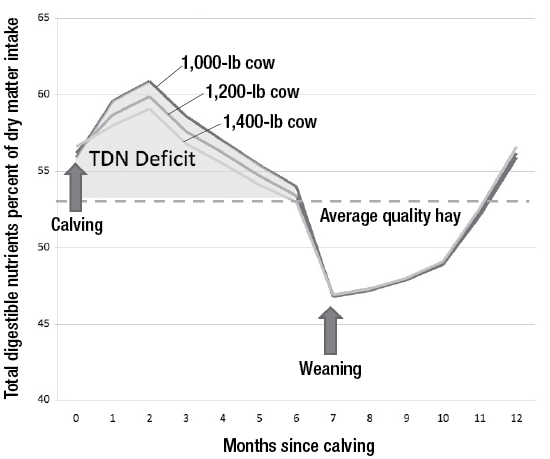

Cattle energy requirements vary with stage of production, size of the animal, and expected performance. Energy as TDN is required for milk production and body maintenance after calving. During lactation, larger cattle typically require more pounds of TDN per day than smaller cattle but as a lesser percentage of their total dry matter intake. Lighter cattle require higher quality feeds and forages at lesser quantities compared with heavier cattle (Figure 3).

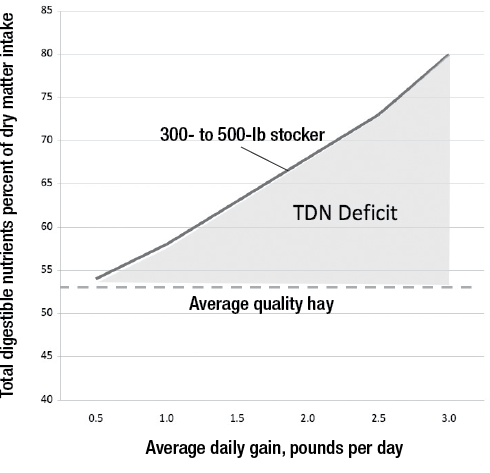

Cattle requirements for TDN increase with increasing lactation and rate of gain (Figure 4). Although there is often a nutrient deficit after calving of both TDN and crude protein when feeding average-quality hay, postpartum cows on forage-based diets are more likely to require longer periods of energy supplementation than protein supplementation.

Young, growing cattle, in particular, need relatively high levels of TDN in their diets to support growth. Additional energy and protein are often required to properly balance diets for growing cattle and lactating beef cows on forage-based diets. This is especially true when low-quality stored forages are the majority of the diet, as is often the case during the winter hay-feeding period after a poor hay production season or with hay produced under low levels of management. Forage quality testing well before feeding is an invaluable tool for determining stored forage TDN concentrations.

Energy Supplements

Energy supplements are available in many forms. High-quality forages, commodity coproduct feedstuffs, range cubes, protein blocks, and liquid supplements are some examples. Diets containing nonprotein nitrogen (urea) must have sufficient carbohydrate levels (energy sources) available in them if the nitrogen in urea is to be effectively used. Consider cost per unit of TDN and convenience of various energy supplements. Base purchasing decisions on the cost per pound of TDN rather than the price per pound of supplement.

Feed product labels do not normally report percent TDN or other energy values. However, producers can still find out TDN estimations to use in nutritional program planning. One option is laboratory nutritional analysis. This service can generally be performed for a nominal fee. Submit forage and feed samples to laboratories such as the Mississippi State Chemical Laboratory or the Louisiana State University AgCenter Forage Quality Laboratory. Another option is to use “book values” from feed composition tables for similar feed ingredients. The Mississippi State University Extension Service can help producers obtain and use this information.

Consider using high-quality forages such as vegetative legumes and cool-season forages to supply TDN in beef cattle diets when possible. If the operation has facilities to store and handle bulk feed ingredients, using commodity-based coproduct feedstuffs usually will be the best value for supplementing forage-based diets for stocker calves and lactating cows. Examples of feedstuffs (and their typical TDN concentrations on a dry matter basis) that can serve as effective energy supplements include corn (90 percent), soybean hull pellets (80 percent), whole cottonseed (90 percent), hominy feed (91 percent), corn gluten feed (83 percent), dried distillers’ grains (86 percent), wheat midds (77 percent), rice bran (70 percent), cane molasses (80 percent), and citrus pulp (80 percent).

Fats are another source of energy in beef cattle diets. When cattle consume too much fat, feed intake may fluctuate, and scouring (diarrhea) may occur. Conservative estimates of maximum recommended fat levels in beef cattle diets are 6 percent for mature cattle and 4 percent for young, growing cattle. Examples of feedstuffs (and their typical fat percentages on a dry matter basis) containing relatively high fat percentages include whole cottonseed (18 percent), rice bran (15 percent), brewers’ grains (11 percent), dried distillers’ grains (10 percent), and hominy feed (8 percent). Feedstuffs high in fat content can be offered in combination with feedstuffs lower in fat content to reduce the overall fat percentage in the diet.

Summary

Digestible energy, as compared to crude protein, is more likely to be deficient in forage-based beef cattle diets in Mississippi. Protein, carbohydrates, and fats serve as energy sources in beef cattle diets. Feedstuff quality analyses and cattle nutrient requirements often use TDN to indicate energy levels. Several types of supplemental energy sources are available for beef cattle diets. Young, growing cattle and lactating cows are classes of cattle most likely to require energy supplementation. Prices, forms, and TDN content of these supplements vary widely. Purchase energy supplements based on price per unit of TDN. Use good management to avoid acidosis problems when increasing the energy content of the diet. For more information on energy in beef cattle diets, contact your local MSU Extension office.

References

Ball, D. M., Hoveland, C. S., & Lacefield, G. D. (2007). Southern forages (4th ed.). Potash and Phosphate Institute and Foundation for Agronomic Research. Norcross, GA.

National Research Council. (2000). Nutrient requirements of beef cattle (7th ed.). National Academy Press. Washington, D. C.

Publication 2504 (POD-04-21)

Reviewed by Brandi Karisch, PhD, Associate Extension/Research Professor, Animal and Dairy Sciences. Written by Jane A. Parish, PhD, Professor and Head, North Mississippi Research and Extension Center; and Justin D. Rhinehart, PhD, former Assistant Extension Professor, Animal and Dairy Sciences.

The Mississippi State University Extension Service is working to ensure all web content is accessible to all users. If you need assistance accessing any of our content, please email the webteam or call 662-325-2262.