Trichomoniasis in Beef Cattle

Bovine trichomoniasis can be costly for beef cattle operations that use natural service. The disease can be found worldwide. It causes extended breeding seasons and diminished calf crops. Infection can be costly to treat, and its prevention is critical to the health of your breeding animals.

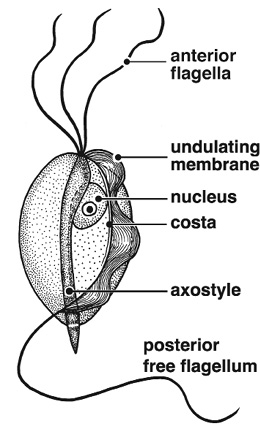

Trichomoniasis (often called “trich”) is a true venereal disease caused by a protozoan organism called Tritrichomonas foetus. It is spread through sexual contact. Adding infected bulls or cows into your herd is the most common source of introduction. Exposure to the neighbor’s bulls through a fence break or common grazing can also be a source of infection.

In cows, the organism lives in the vagina, cervix, uterus, and oviducts. Infected cow herds experience infertility, pyometras (uterine infections), and early abortions. Breeding usually results in conception, but pregnancy losses occur during the first few weeks of gestation, resulting in repeat breeders and inconsistent calving distributions. Sometimes, cows have a white vaginal discharge following initial infection.

The reservoir for this organism is the persistently infected bull. The organism lives in the internal sheath and skin folds of the bull’s penis. As bulls age, the skin folds grow, giving the organism more places to grow and thrive. Therefore, older bulls (that is, bulls more than 4 years old) are more likely to be persistent or chronic carriers of the disease. In older bulls, it is a lifelong infection and can be transmitted from one breeding season to another if left undetected. Trichomoniasis causes no clinical signs in the bull and does not affect sexual behavior or semen quality.

Identifying persistently infected bulls can be difficult. To diagnose infection, a preputial scraping is taken from the sheath of the bull’s penis. A culture or polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) test is then performed on the sample. Three separate culture tests, each conducted not less than 1 week apart, or one PCR test should be performed.

A bull undergoing three separate culture tests must be negative on each test to be considered free of trichomoniasis. Cultures taken at 1-week intervals for 3 weeks will identify most infected bulls. Studies have shown that a single culture will miss about 10 to 20 percent of infected bulls. The sensitivity (ability to correctly identify positive animals) of Trichomonas culture using current commercial media has been estimated as 70 to 97 percent. Therefore, current testing recommendations suggest that you can be approximately 99 percent sure that your bull is negative after three negative tests. PCR is a newer, faster testing method for detection of the organism, but its availability and use may vary among laboratories.

There are no approved treatments for infected bulls or cows. A vaccine is available for trichomoniasis, and studies suggest that the vaccine may decrease the duration of shedding and prevent some pregnancy losses in cows. The vaccine does not appear to be effective in bulls. Given the lifelong nature of bull infections and lack of approved treatments, slaughtering infected bulls is recommended. Cows often clear the infection naturally with several months of sexual rest; however, immunity does not last long and they are susceptible to reinfection.

As a sexually transmitted disease, trichomoniasis can be controlled by good biosecurity and breeding management. Artificial insemination using semen from reputable bull studs is an effective way to prevent sexually transmitted diseases. Rare cases of disease transmission through contaminated semen or AI equipment have been reported. To prevent the spread of the disease when breeding cows naturally, use virgin bulls that have never been pastured or housed with a bull that has bred a cow. If non-virgin bulls must be brought onto the farm, follow a rigorous testing and quarantine protocol.

To control trichomoniasis in an infected herd, identify positive animals and remove positive bulls. If one bull is found infected, then the rest of the herd is probably also infected. Quarantine and enforce sexual rest for females exposed to or suspected of carrying the disease. Quarantine alone will not protect your herd because there are few symptoms to help you identify infected animals.

These practices can also help control reproductive disease: maintaining a defined breeding season and performing pregnancy exams, culling open cows, not purchasing older cows or bulls, performing a breeding soundness exam (BSE) on all bulls before the breeding season, and not sharing or leasing bulls.

Keep good records of a herd’s reproductive efficiency. Pregnancy rates and service records can help identify potential reproductive problems. You may notice bulls servicing cows later in the breeding season, decreases in pregnancy rates, spread-out calving seasons, or highly variable weaning weights. Several conditions can cause these signs in cattle, and it is important to work with your herd veterinarian to maintain your herd’s reproductive health.

Should You Be Concerned?

Trichomoniasis has been a problem in beef herds for many years. It is most common in western and southern states, where open rangeland, extensive grazing practices, and natural breeding have allowed infected animals to spread the disease. The disease appears to be spreading south.

Several states have implemented trichomoniasis control programs and mandatory testing for breeding animals. If you are traveling with your animals to a state that requires testing, you should contact the state animal health official several weeks in advance to see which test is acceptable. Furthermore, if you rely on natural service, consider implementing a testing and control program for your herd.

The information given here is for educational purposes only. References to commercial products, trade names, or suppliers are made with the understanding that no endorsement is implied and that no discrimination against other products or suppliers is intended.

Publication 2609 (POD-11-23)

By Carla L. Huston, DVM, PhD, dipl. ACVPM, Professor and Beef Extension Veterinarian, College of Veterinary Medicine, and Kevin Walters, DVM, dipl. ACT, Assistant Clinical Professor, College of Veterinary Medicine.

The Mississippi State University Extension Service is working to ensure all web content is accessible to all users. If you need assistance accessing any of our content, please email the webteam or call 662-325-2262.